Two Brown professors have perfected a treatment for the most severe kinds of strokes. Now they’re working to change the way stroke patients are triaged so they can get the procedure as quickly as possible.

On Sept. 3, 2018, Lori Camara had a stroke. After her husband called 911, she was rushed by ambulance to the nearest hospital.

This may seem like the most logical thing to do. A patient is in distress, take her to the closest place she can get care—except that hospital couldn’t give her the care she needed. That’s because Camara, 53, was having an emergent large vessel occlusion (ELVO) stroke, a serious type of stroke that comes with high rates of incapacitation, morbidity, and mortality.

Fortunately, the hospital knew to obtain a CT angiogram, a scan that images blood vessels and tissues. It showed that she was in dire shape, so she was rushed to Rhode Island Hospital for a mechanical thrombectomy, a procedure that removed the clot blocking blood flow to her brain.

Two days later, she was discharged. “I’m a miracle. I’m very blessed,” she says from her home in Westport, MA, in February.

Until recently, the outcome of such cases has been bleak. Overall, stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the US, killing about 142,000 people per year, according to the American Heart Association, and 5.5 million people worldwide. Stroke is also the leading cause of long-term disability in the US. A lot of that damage is done by ELVO strokes. Even though ELVOs only cause about a third of acute ischemic strokes, they are responsible for three-fifths of dependency and more than nine-tenths of stroke deaths.

If blood flow can be restored, though, patients are more likely to avoid such a fate. For Camara, that meant instead of being in a nursing home or worse, she could talk on the phone about her experience while waiting for her sister to pick her up for a girls’ weekend, five months after she left the hospital.

“I can’t believe I’ve recovered to the extent that I have,” she says.

DRAMATIC RESULTS

Strokes come in two different forms: hemorrhagic, caused by bleeding; and ischemic, caused by a clot or narrowing of an artery.

In ELVO strokes, the arteries involved “feed a large part of the brain, and it’s oftentimes the tissue in those areas that control things like movement for half of the body, vision, and language,” says Karen L. Furie ’87 MD’90 RES’94 F’95, P’19MD’23, MPH, the Samuel I. Kennison, MD, and Bertha S. Kennison Professor of Clinical Neuroscience and chair of the Warren Alpert Medical School’s Department of Neurology.

With the brain starved of nutrients and oxygen, “these patients were often devastated. They’d be institutionalized, unable to swallow, unable to care for themselves,” she says.

Right now, only about 3 percent of ischemic stroke patients are treated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a clotbusting medication that typically works well for small clots. But, says Mahesh V. Jayaraman ’94 MD’98 RES’03, director of the Neurovascular Center at Rhode Island Hospital and associate professor of diagnostic imaging, of neurology, and of neurosurgery, it doesn’t have a significant effect on large blockages. Patients with severe strokes have about a 25 percent chance of having a good outcome if tPA is administered in the first hour after symptoms present.

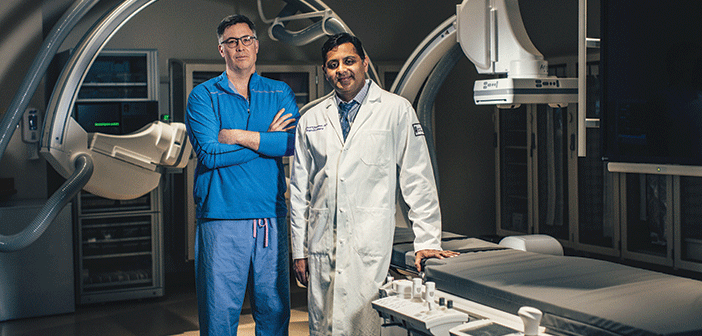

That’s where mechanical thrombectomy comes in. The technique was refined by Jayaraman and Ryan A. McTaggart RES’10, MD, director of interventional neuroradiology at Rhode Island Hospital and an associate professor of diagnostic imaging, of neurology, and of neurosurgery.

The procedure seems relatively simple: Using fluoroscopy—a continuous X-ray—a neurointerventionalist snakes a catheter from an artery in the upper leg to the brain and then deploys a stent retriever within the clot to snare it and pull it out.

The process takes under an hour, is minimally invasive, and patients sometimes go home the next day. Camara went home after two days because her treatment also involved repairing a dissection (or tear) of her carotid artery.

Mechanical thrombectomy has been wildly successful. In 2015, five randomized trials “all reached the same conclusion, and that is that the modern thrombectomy devices dramatically improve the likelihood of a good outcome compared with medical therapy alone,” Jayaraman says.

“It’s like a blocked pipe. You can restore flow and prevent the brain from dying,” Furie says. “It’s a very effective way of rapidly restoring blood flow.”

Camara is an example of the astounding treatment effect. After undergoing subsequent physical therapy and speech therapy, she says that the lingering side effects are minimal compared to what they could have been, and she plans to return to her job teaching seventh-grade students in the near future.

Going from not being able to do anything to doing something—with such proven results—is not just uncommon but extraordinary, says Jayaraman.

“It’s one of the most profound treatment effects in all of medicine,” he says. “You rarely get a flip-of-the-switch moment where you go from no evidence supporting a treatment to dramatic evidence showing superior outcomes.”

TIME IS TISSUE

As astounding as the results of mechanical thrombectomy have been, getting patients to the interventional suite as fast as possible to get the procedure is critical for it to work. The chance for a good outcome drops 15 percent for every hour the procedure is delayed. Every minute counts, Jayaraman says, because “if you save a minute, you save the patient a week of independent life.”

“When we restore blood flow quickly we not only reduce disability but we can also save downstream health care costs. Every minute faster we open that vessel, we save the health care system more than $1,000—each minute faster!” McTaggart adds.

In order to save those minutes, patients need to be taken as soon as possible to a comprehensive stroke center where a mechanical thrombectomy can be done—there are 175 such centers in the US—and not to a primary stroke center.

Confusing the two is easy, especially when there are more than 1,000 primary stroke centers in the country. They have 24/7 CT and MRI capabilities and can give patients tPA, but they are not required to be able to perform mechanical thrombectomy to receive their primary stroke care center designation.

“For the first time in medicine, we have a unique problem. You have a highly effective treatment—if the patient gets it,” Jayaraman says. According to a 2017 poll, 33.8 percent of EMS providers said they most frequently took stroke patients to the nearest hospital.

Making changes to stroke systems of care in order to get patients with ELVO strokes to a comprehensive stroke center as soon as possible has required a rethinking, from start to finish, of how stroke patients are evaluated and how long it takes them to get into the neurointerventional suite.

“What we need to do is transform the systems of care so that patients have early access to this lifesaving surgery,” McTaggart says.

That’s why he and Jayaraman have become evangelists for the importance of identifying ELVO strokes and getting those patients to comprehensive stroke centers, doing everything from lobbying local governments to change medical protocols to McTaggart naming his Twitter account @mobilestroke4U. Using the hashtag #leavenoELVObehind he tweets about the need to change strokecare delivery and champions mobile stroke unit technology.

There is precedent for this kind of protocol change, McTaggart says. He points out that someone with chest pain is given an electrocardiogram (ECG) to detect STEMIs (the most severe heart attack) and those patients are triaged directly to centers that offer interventional cardiology, and that people in rollover car crashes are sent to Level 1 trauma centers by default.

“But the world has lagged on understanding that in two minutes you can do a CT angiogram [CTA] that will confirm or exclude the worst possible stroke a patient can have,” he says. “CTA is to ELVO what ECG is to STEMI.”

Their work, of course, started in Rhode Island, which in 2015 became the first state to triage stroke patients directly in the field. In 2017, the Rhode Island Department of Health changed the statewide Emergency Medical Service protocols so that patients with suspected ELVO strokes are sent directly to the closest comprehensive stroke center (right now Rhode Island Hospital is the only one in the state). Similar protocols have since been put in place in other states.

McTaggart has taken a hands-on approach to make sure those who can make a difference understand the importance of these changes, why they happened, and what they can do to get patients into the right care faster, and then put them into practice.

“Legislation and regulation doesn’t always translate into behavior, so we’re trying to change behavior by literally going to every single fire station in the state and educating them on what an ELVO stroke is, what the mechanical thrombectomy is, and teach them how to recognize patients with severe stroke,” he says.

That includes teaching emergency professionals how to use the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS) score, which evaluates things like facial droop, arm lift, and grip strength. Patients rated four or five, on the one-to-five scale, should immediately be sent to a comprehensive stroke center. McTaggart also has them simulate calls about their patients, making sure they’re conveying appropriate information, like when the patient was last seen well, their LAMS score, if they’re on anticoagulants, their blood pressure, date of birth. For this work, McTaggart received the Rhode Island Hospital Service to Community Award last year.

They’ve collaborated with primary stroke centers to identify those with ELVO stroke who come to their hospitals first, which resulted in cutting 40 minutes off the median time to get a patient from a primary stroke center to

Rhode Island Hospital.

“Mahesh and I felt a responsibility to work with all our partner hospitals to enable them to better make this diagnosis and improve their efficiency so people wouldn’t suffer unnecessary death and disability,” McTaggart says. “The only thing more frustrating than missing the diagnosis entirely is witnessing a prolonged interfacility transfer so that the brain is dead by the time they get to us.”

Such efforts most likely saved Camara’s life when she was first taken to the hospital closest to her home. That hospital executed the primary stroke center ELVO protocol: they performed a CT angiogram as soon as she arrived, which showed an ELVO stroke, and she was rushed to Rhode Island Hospital, where she immediately underwent a mechanical thrombectomy.

“She would have been neurologically devastated or probably dead had she not gotten here to have the procedure,” McTaggart says. “Rather than 40 years of living in a nursing home, she’s going to be back to work and doing everything she did before this happened.”

WHAT’S NEXT

While the mechanical thrombectomy has consistently improved outcomes for ELVO strokes, Jayaraman and McTaggart are still working to refine it, improve access, and optimize techniques, such as whether adjuvant medical therapy can improve outcomes.

Rhode Island Hospital was the second-highest enrolling site of patients into the DEFUSE 3 trial. The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, showed that physicians should extend the window for treatment of ELVO strokes with mechanical thrombectomy from six hours from the onset of symptoms to 16 and 24 hours. It has also made a major difference for what’s known as “wake up” stroke patients, where the time of onset of stroke symptoms is not known. The results “really change the entire philosophy. Time doesn’t matter. What matters is what the imaging shows,” McTaggart says. If a CT scan shows that the brain tissue hasn’t died yet, they’re candidates for this procedure. “It can save them from death and disability,” he says. “The tissue is the issue.”

Rhode Island Hospital is also a top enrolling site of patients into the ESCAPE-NA1 clinical study. It’s an ongoing phase 3 trial testing the safety and efficacy of using NA-1, a neuroprotectant, along with mechanical thrombectomy, in ELVO stroke patients (Camara is enrolled in this study). It’s also assessing whether the use of NA-1 leads to lower rates of needing dependent care, improved neurological function, improved activities of daily living, and lower mortality rates.

The doctors continue to advocate for better field assessment of stroke patients, with two end goals. The first is the creation and deployment of mobile stroke units, which are ambulances outfitted with a CT scanner and telemedicine capabilities, something McTaggart calls the “holy grail of stroke care, where the highest-level expertise is delivered right to your driveway.”

“It’s a primary stroke center on wheels,” Jayaraman says. It would allow EMS to obtain a CT scan and identify ELVO strokes at the point of first interaction with medical personnel, and therefore get them sent to the most appropriate center as soon as possible.

The second goal is legislation in all geographic regions to get every patient, regardless of their location, access to mechanical thrombectomy and the highest level of stroke care. “In major metro areas, that means field triage and bringing patients to the right place the first time,” McTaggart says, while more remote areas will rely heavily on protocols and telemedicine so that patients are diagnosed early when they arrive to hospitals and can be rushed to comprehensive stroke centers for the intervention.

At the very least, every hospital should be doing a CT angiogram for every single stroke patient assessed, he says, which is already the standard at Rhode Island Hospital.

“I like to say that stroke is just as devastating as the most severe cancer, but unlike cancer, we have a cure,” McTaggart says. “We’ve taken up this call and we’ve done all this education and sacrificed our own personal lives and sleep patterns so we can protect patients from something that’s now totally reversible.”