A Brown psychiatrist helps bring PTSD treatment to Ukraine.

On the eve of his trip to Ukraine last November, Noah Philip RES’09, MD, packed nervously. The bulletproof hoodie he’d bought online would be as useful as his Oxford shirts in the event of a Russian missile strike. And the tools of his trade—a textbook, training packets, and tape measures—made for a meager kit compared to the enormity of his mission.

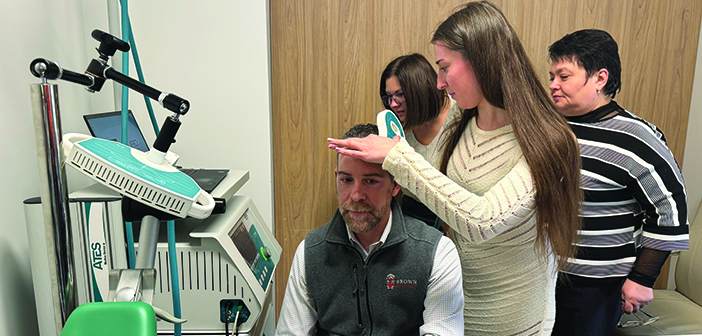

Philip, a Brown professor of psychiatry and human behavior and a psychiatrist at the VA Providence Healthcare System, had been invited to Ukraine to share his expertise in transcranial magnetic stimulation, a non-invasive treatment for PTSD that uses magnets to alter brain activity. His specific charge was to teach providers at a hospital in Lviv how to use their TMS machine—an old, donated Italian model of hazy provenance that was so prone to overheating, hospital staff were afraid to use it.

Yet he couldn’t let them down. The need for trauma relief in Ukraine is extensive—veterans returning from the front lines, torture survivors, and civilians living under constant threat of attack.

“A core Jewish value in my heart is the spirit of tikkum olam, or ‘repairing the world,’” Philip says. “The singular goal of my career is to make this world a better place. Here was an opportunity to do exactly that, but on a scale I never thought would be available to me.”

Philip traveled to Lviv with two colleagues from Yale at the behest of Unbroken, a nonprofit founded by two military volunteers who had lost limbs in the war. In the psychiatry unit, Philip met patients coping with raw, deep traumas. One patient, a military sergeant, had just lost three limbs and stayed up each night to guard his roommates. Many torture survivors had gone completely mute.

“I saw EEGs that showed a complete absence of normative brain rhythms,” Philip says. “I’ve never seen anything like that.”

Before he could train the hospital team to use their TMS machine, Philip had to determine what it could do. Straightaway, he discovered that it emitted weak energy, meaning the first step in a TMS treatment—the motor threshold test—would pose an extra challenge. Instead of conducting a simple finger-twitch test to establish a patient’s motor threshold, they would have to use an electromyogram, a complicated electrode-involved workaround that Philip hadn’t used in a decade.

Philip created algorithms the Ukrainians could use to calculate how much energy was needed, for how long, and for which patient motor thresholds. He even offered himself as a test subject while training the Ukrainian team on their finicky TMS machine.

In a matter of days, Philip trained the clinicians to provide TMS care—instruction that would normally unfold over a month with Brown psychiatry residents. He left them with learning materials, notes, and skills checklists, and designated a point person to contact him as questions arose.

“Initially, only physicians were using their TMS machine,” Philip says. “Now, after a physician establishes a patient’s motor threshold, a technician should be able to deliver TMS. That allows you to increase your scale considerably.”

Philip has continued to collaborate with Unbroken, connecting them with a manufacturer of reliable TMS machines and raising funds for new devices. He is also helping them pursue avenues of research into their innovative treatments. “Their ideas could be really helpful for other complex conflict zones,” he says.

Meanwhile, he believes the research conducted at Brown can help the Ukrainians as well. “Here, we see particularly terrible PTSD in veterans who were not professional soldiers—people who were in the private sector one day and in a war zone the next,” Philip says. “That’s the entire Ukrainian military. It’s going to be an enduring challenge they’ll be dealing with for decades. But I think much of what we’ve learned can really help them.”