Research in aging mice suggests HIV medication has potential to treat age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s.

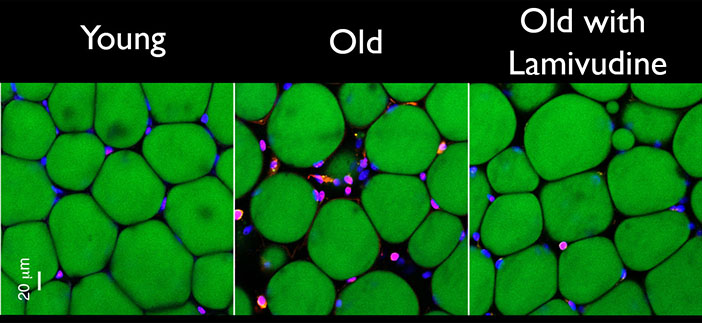

A new study found that lamivudine, a generic HIV/AIDS drug, significantly reduces age-related inflammation and other signs of aging in mice.

“This holds promise for treating age-associated disorders including Alzheimer’s,” says John Sedivy, PhD, professor of medical science and of biology. “And not just Alzheimer’s but many other diseases: type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s, macular degeneration, arthritis, all of these different things. That’s our goal.”

Age-related inflammation is an important component of age-associated disorders.

The findings were published on February 6 in Nature. The collaborative research project included researchers at Brown, New York University, the University of Rochester, Université de Montréal, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, and Leiden University Medical Centre in The Netherlands.

According to Sedivy, lamivudine acts by halting retrotransposon activity in old cells. Retrotransposons—DNA sequences able to replicate and move to other places—make up a substantial fraction of the human genome. Retrotransposons are related to ancient retroviruses that, when left unchecked, can produce DNA copies of themselves that can insert in other parts of a cell’s genome. Cells have evolved ways to keep these “jumping genes” under wraps, but as the cells age, the retrotransposons can escape this control, earlier research from Sedivy’s lab showed.

In the Nature paper, the research team showed that an important class of retrotransposons, called L1, escaped from cellular control and began to replicate in both senescent human cells—old cells that no longer divide—and old mice. Retrotransposon replication, specifically the DNA copies of L1, is detected by an antiviral immune response, called the interferon response, and ultimately triggers inflammation in neighboring cells, the researchers found.

These retrotransposons are present in every type of tissue, which makes them a compelling suspect for a unified component of cellular aging, Sedivy says. Understanding that, the team uncovered the interferon response, the potential mechanism through which these jumping genes may cause cellular inflammation without necessarily causing damage to the genome.

“This interferon response was a complete game changer,” Sedivy says, noting that it is hard to track where newly inserted transposable elements may have inserted themselves in a genome that contains a vast number of inactive and active retrotransposon sequences.

Continue reading here.