Preeclampsia—and its sometimes fatal outcomes—have baffled physicians for ages.

“Here lies Margaret Robinson, daughter of Arthur Robinson, Knight, of the county of York, and wife of Robert Jegon Esquire, with whom she was joined in the most chaste bond of married love for the space of nine years and, after she had most happily given birth to five children, her sixth offspring died while still enclosed in her womb. After being shaken by the force of frequent convulsions, she gave up her soul to heaven on the fourth day of December AD 1638.”

—from Pre-Eclampsia: The Facts

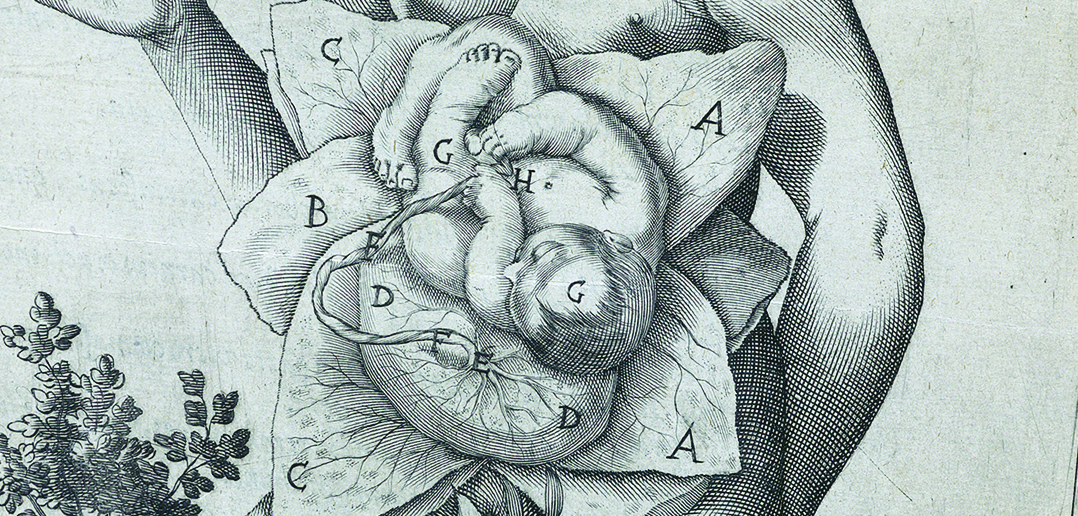

In the 17th century, “died in childbirth” would have been the epitaph for one in eight mothers, and there was little that medical ingenuity at the time could do about it. Most treatments relied on the dominant theory that illness resulted from an imbalance of the body’s four humours—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—a theory that modern science has long since discarded. There were no regular medical checkups during pregnancy, and there was no way physicians could properly diagnose pregnancy disorders. Besides bloodletting to balance the humours, physicians had little to offer expectant mothers.

Many of the problems that arise in pregnancy are understood and treatable today, but one is not: preeclampsia, the disease that killed Margaret Robinson in 1638. Marked by high blood pressure and resulting organ damage, preeclampsia is the most common pregnancy disorder worldwide and the leading cause of infant and maternal death in the US. Once known as the “toxemia of pregnancy,” preeclampsia can cause lethal seizures if left untreated, and the only effective treatment is immediate delivery of the baby. (In the television series Downton Abbey, Lady Sybil died in a fit of seizures after her family refused to allow this emergency measure.) But if ending pregnancy early can save the mother, it can be disastrous for the infant. Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant mortality and neurological disabilities in children.

Modern medicine has not erased the specter of death from motherhood, and three centuries after it was first described by physicians, preeclampsia remains a heartbreaking dilemma. Scientists have yet to unravel the causes of this mysterious disease.

A Unique Partnership

“There are two important enigmas in pregnancy—preterm birth and preeclampsia. This is despite decades of research on both disorders,” says James Padbury, MD, the William and Mary Oh–William and Elsa Zopfi Professor of Pediatrics for Perinatal Research, professor of pediatrics, and chief of Pediatrics at Women & Infants Hospital. Researchers know preeclampsia as “a disease of theories,” and struggle to come up with a simple explanation for the condition.

Preeclampsia does not have a single cause; instead, various abnormalities build in the mother like themes in a symphony until the condition finally surfaces, like the crescendo of a dissonant chord. Scientists have observed that preeclampsia runs in families and is more prevalent in first-time mothers, but no one has tied specific genes to the disorder. Scientists also have looked to the presence of free radicals and inflammation in the uterus and malfunctions in the mother’s immune response during pregnancy as possible culprits. The abnormal constriction of the fine vessels that circulate essential nutrients to the placenta also may contribute to the disease.

“When blood flow is abnormal in the placenta because of preeclampsia, you can also get abnormalities in blood flow in other parts of the body, even in the brain,” Padbury says. Scientists agree that preeclampsia arises in part because of a failure in the unique partnership between a pregnant woman and her unborn child.

The path to motherhood wasn’t an easy one for Brittany Josey. On a Sunday night in May 2011, Josey checked into the emergency room at Caritas Good Samaritan Hospital in Brockton, MA, after enduring months of a terrible cough. Only six months before, she’d had surgery to remove an intrauterine device, which had punctured her uterus. Now Josey was lying in an examination room in the same hospital with a diagnosis of bronchitis. And she received some startling news: she was pregnant.

During her examination, Josey felt a sharp pain when the nurse palpated her right side—her right fallopian tube had ruptured. Josey was suffering from an ectopic pregnancy, a life-threatening disorder that affects about 1 in 50 pregnancies. In an ectopic pregnancy, the embryo does not make the full journey to the uterus and instead implants in the fallopian tube. Her doctors rushed her into emergency surgery, which can save the mother, but the chances that the baby will survive are slim. At 22 years old, Josey had lost her first child, and her doctors told her that she would never have children again.

“It didn’t matter whether I wanted children,” Josey says. “Just knowing I would never have children was depressing.” But after a year, things were starting to get back to normal. She was seeing somebody new and wanted a fresh start. After commuting to New York from Boston to be with her boyfriend, Josey finally made the decision to stay. She moved to the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, and settled into the expense and bustle of New York. “I started to accept that I would not have children,” she says.

The Sick Placenta

Preeclampsia begins with a breakdown in the machinery of the placenta, which delivers nutrients and oxygen to the fetus during pregnancy. The placenta also fends off infections, and is an important organ for protecting the fetus from vagaries in the maternal environment, Padbury says. A healthy placenta is crucial for a successful pregnancy.

“Everything needs to be in balance during pregnancy,” says Elizabeth Triche, PhD, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Brown and a researcher at Mount Sinai Rehabilitation Hospital in Hartford, CT. Triche studies the environmental and genetic underpinnings of pregnancy disorders like preeclampsia. Early in pregnancy, the mother has to grow accustomed to the presence of the fetus. The human body normally cannot bear the presence of foreign cells, and the aggressive response of the white blood cells that patrol our circulation is what causes the fever and aches of illness. Scientists speculate that preeclampsia may be a result of intolerance against the fetus, a glitch in the immune response that treats pregnancy like a threat. “The mother’s body may see the fetus as a fast-growing tumor,” Triche says. “We do not know if that is true, but that is the hypothesis.”

In a normal pregnancy, five days after the sperm fertilizes the egg, the resulting embryo moves through the fallopian tube to the uterus. The embryo is no larger than a speck of dust, and after embedding itself in the uterine wall it releases cells called trophoblasts into the uterus. Every trophoblast mines deep into the uterine wall, searching like roots through soil and forming a network of fine vessels that will eventually become the tendrils of the placenta. In preeclampsia the roots do not go deep enough, and the placenta begins to shrivel.

Meanwhile, preeclampsia often causes problems elsewhere in the body—symptoms that act as early warning signs of the disease. Headaches and nausea are common as a woman’s blood pressure rises. But a lack of symptoms is an unfortunate marker of preeclampsia, and physicians must rely on experience to spot the condition early. “Women could be totally asymptomatic,” says Kenneth Chen, MD, assistant professor of medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, who leads the Division of Obstetric and Consultative Medicine and the Integrated Program for High Risk Pregnancy at Women & Infants Hospital. “Or they could wake up in the morning not feeling quite right but with no specific symptoms,” he says. The most concrete symptoms of preeclampsia are hypertension and protein in the urine, a sign of kidney damage, and these usually do not present until 20 weeks into pregnancy. But preeclampsia is unpredictable, and these symptoms may not appear until a pregnant woman is dangerously ill—and even then she may be unaware of them. “There’s no such thing as a standard textbook presentation,” Chen says.

In severe cases of the disease, a woman can become delirious and suffer seizures, known as eclampsia. Nearly 8,500 deliveries occur at Women & Infants each year, and “preeclampsia affects up to 10 percent of all pregnancies,” Chen says. “That’s about 800 people a year, and I have two patients with this on my service right now.”

On August 21, 2013—more than two years after her emergency surgery—Brittany Josey made a startling observation: her period was late. On a break at work, she went to a drug store and bought a pregnancy test. “I felt my heart stop twice in my chest,” she says. Josey was going to be a mom.

At first, she was afraid her pregnancy would end her relationship. “I debated if I should tell my boyfriend,” she says. “I waited a couple of days, but when he heard, he was really excited, and I thought, maybe I am really excited, too.”

She worried that the previous ectopic episode would cause new problems for her pregnancy. She had regular prenatal visits, and a mother who called and worried about her constantly. “I took care of myself,” Josey says. “I had no abnormal tests and I never heard anything about possible complications.” But toward the end of her second trimester Josey began to worry something was wrong. “My hands got tight,” she says, “and I couldn’t walk without feeling like I was going to pass out.” Even so, her doctor reassured her that she was fine. Her last prenatal visit was on February 25, 2014, and despite her anxiety, all of her tests came back negative for any complications. “I wrote off these feelings,” she says, and with her doctor’s blessing she traveled to Rhode Island to celebrate her baby shower.

A few days later her symptoms worsened. “I was having sharp pains beneath my chest,” Josey says, “and my hands and feet were swelling a lot more. My heart raced even when I was sitting down.” Although she was only six months pregnant, Josey looked as if nine months had flown by. Her family urged her to see a doctor to be safe, but she hesitated. “I held off,” she remembers. “I didn’t think it was anything just yet.” Finally she agreed to go to the emergency room at Women & Infants, and within minutes she was on her way to intensive care. She had severe preeclampsia.

In Search of a Cause

The landscape of preeclampsia research is like an unfinished jigsaw puzzle, with clearly defined parts and much more empty space. One thing that is known is that preeclampsia shares much of its pathology with cardiovascular disease. Preeclampsia triggers the release of harmful molecules from the placenta that prevent the proper formation of blood vessels. Many of these molecules worsen the blood vessel constriction that causes hypertension in the pregnant mother. But, while many of these factors are significant, “each may be a consequence of the disease rather than a cause,” Triche says. Any promising marker for preeclampsia may turn out to be just another symptom in the whirlwind of inflammation engulfing the uterus.

It would be helpful if researchers could study the condition in animals, but preeclampsia only occurs in humans. Although scientists have studied a variety of animal models for preeclampsia, to date none of the models fully duplicates its progress in pregnant women. In a 2010 study published in The American Journal of Pathology, researchers at Women & Infants honed in on a promising animal model for the disease. Scientists built on research linking the presence of the immune molecule interleukin-10 (IL-10) to a successful pregnancy, and began experimenting with mice genetically engineered to lack IL-10. After giving a dose of blood serum from women with preeclampsia to these mice during pregnancy, they developed preeclampsia-like symptoms. “Our model is the first pregnancy-specific animal model for preeclampsia, a devastating complication of pregnancy,” says Surendra Sharma, MD, PhD, the senior author of the study and professor of pediatrics at Alpert Medical School.

Researchers remain frustrated by their inability to mimic the conditions of a human pregnancy in an animal. But they press on. If they can identify a mechanism, they can get at treatment, prediction, and even prevention, Sharma and Padbury say.

By the time Brittany Josey was admitted to Women & Infants, her body was swollen from her feet to her face. In three days, she had gained 40 pounds. Her doctors could not do anything to bring down the swelling, but they immediately put her on a treatment of magnesium sulfate, which—for reasons still unknown—prevents seizures.

At that point, Josey was just 32 weeks into pregnancy, and her doctors wanted her hospitalized until delivery. As almost always occurs in preeclampsia, the doctors would have to balance her health with the baby’s welfare. “Because my condition was so severe, they were going to keep me pregnant for under two weeks,” she says; the baby would be born five weeks early. To prepare for the early delivery, doctors also treated her with corticosteroids, which help the infant’s lungs develop faster and greatly increase the chances that a preterm baby will survive.

Days in the hospital passed in moments of boredom and apprehension. The magnesium left a taste in her mouth like a pocketful of coins, Josey recalls. “Everything felt repetitive, and I was miserable from being swollen,” she says. Apart from weekend visits from her boyfriend and frequent calls from her mother, she spent her days waiting, and had to Skype into her own baby shower. “There was no telling how fast or slow everything would be,” she says. After several days, her doctors decided she was stable enough to discontinue the magnesium sulfate.

One day later, on a gray Providence morning, Josey was having a quiet breakfast. “I got up to use the restroom, and that was the last thing I remembered,” she says. When she came to, she was on the bathroom floor and her head was ringing. “I was being picked up off the floor of the bathroom and my right arm was twisted behind me.” She’d had a seizure.

The Smoking Gun?

“Preeclampsia has clear evidence for a genetic underpinning,” Padbury says. Researchers and clinicians have long suspected that there are genetic differences between mild and severe preeclampsia, and Padbury’s recent research suggests that the genes involved fall into distinct genetic clusters. Using bioinformatic techniques to sort through thousands of scientific records about the genetics of preeclampsia, Padbury and his team identified target genetic clusters in a comprehensive 2014 paper published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. “It is better to start with a cluster of genes we know are associated with preeclampsia,” Padbury says. With his findings as a resource, scientists can narrow their search to hundreds rather than thousands of genetic targets.

Yet the search for a cause cannot advance without molecular evidence—a molecule that could network the many theories about preeclampsia. Such evidence may be emerging from Sharma’s laboratory, whose 2014 study in The American Journal of Pathology sheds new light on the condition. “We are trying to approach preeclampsia from different angles,” Sharma says. The most interesting one seems to be the discovery of a novel glitch that occurs in preeclampsia: the misfolding and aggregation of a protein that is normally harmless and present in every individual. This protein, transthyretin, shuttles hormones to different organs in the body and is crucial for a healthy pregnancy.

“If the fetal brain does not receive the hormones it needs, the newborn will develop serious neurological issues,” Sharma says. “We have found that transthyretin is not present in the same way during preeclampsia as it is in a normal pregnancy. When this protein misfolds, it can undergo aggregation. That is the toxic form of the protein, and it deposits in the placenta. Transthyretin could be a member of a group of proteins that undergo aggregation in response to adverse intrauterine milieu.” Scientists have long suggested that preeclampsia is an inflammatory condition, but this is the first time misfolding and aggregation of a protein have been associated with the disease.

There are several reasons why misfolded transthyretin is such a promising lead. Along with evidence that the toxic form of this protein builds up in the placenta of preeclamptic women, misfolded transthyretin also triggers cell death and may cause the release of other harmful molecules that circulate in mothers with preeclampsia—a rare instance of a molecule that could be a prime mover among the pathways known to contribute to the disease. “The whole cascade can be completed by keeping one or two molecules at the center,” Sharma says. “Different molecules can bring about different changes, but they may all be interlinked in the end.”

Sharma, the principal investigator behind the transthyretin research, is looking to translate these findings into a clinical test. “If we can detect toxic protein aggregates during the early stages of pregnancy,” he says, “it can be used as a marker for preeclampsia.” Sharma’s research with the IL-10-negative pregnant mouse model also revealed that the healthy form of transthyretin can inhibit and reverse preeclampsia symptoms caused by toxic transthyretin. While the animal model limits the finding, and the exact mechanism behind this remedy is still unclear, it presents an opportunity to explore transthyretin as a possible treatment for the disease. Scientists speculate that certain women could be genetically predisposed to misfolded proteins, offering yet another possible avenue to predict the disease.

Misfolded proteins, known as amyloids, also play a part in a number of disorders normally associated with the later stages of life. Amyloid deposits are seen in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, an exciting observation amid mounting research that traces abnormalities in brain development to the earliest stages of pregnancy. Recent findings suggest a specific link between dysregulated transthyretin and Alzheimer’s disease, a disorder of amyloid deposits in the brain. Published in 2013 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, the study details the effects of treating mouse models for Alzheimer’s with healthy transthyretin. The results were strikingly similar to Sharma’s findings with preeclampsia: healthy transthyretin inhibited Alzheimer’s-like symptoms in the mice. Research directed by Sharma and Padbury about the relationship between preeclampsia and Alzheimer’s is still ongoing, but these findings may offer clues to understanding the higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in women.

Children whose mothers had preeclampsia are also often at a higher risk for neurological disorders, and women who have had preeclampsia have double the risk for heart disease and stroke during the 15 years after treatment.

Brittany Josey’s life—and that of her child—were once again in danger. She had hit her head on the floor after the seizure, and her memories blurred with pain and confusion. Doctors and nurses flooded her room and began to prepare her for an emergency delivery. “It took me a while to realize what was happening,” she says. “I remember a room full of people telling me to push.” Three pushes later, a little after 5 a.m. on March 11, 2014, her son, Liam, was born.

Liam had many of the problems of premature birth. He was 4 pounds, 11 ounces, and soon began losing weight. He was jaundiced and had trouble feeding. “He was just so tiny,” Josey remembers. “I was afraid to hold him.” Her son also struggled to sustain his own body temperature. Meanwhile, doctors continued monitoring Josey, who was at risk for another seizure, and whose blood pressure was still dangerously high.

Slowly Liam recovered, and Josey suffered no more seizures. After waiting two weeks, she finally was able to hold her baby.

The Future of Preeclampsia

As clinicians hone their experience and researchers test their theories, women with preeclampsia have few options. In 2010, a large National Institutes of Health-funded trial ruled out recently proposed preventive therapies for preeclampsia—vitamin C and vitamin E. Now researchers are examining chocolate as a protective supplement against preeclampsia. When pregnant women eat chocolate, one of its molecular byproducts, theobromine, increases in the body. “We found it to be strongly protective against preeclampsia,” Triche says. Now the challenge is translating this dietary therapy into a treatment regimen.

Studies have shown that exercise and weight control also may help prevent preeclampsia, but preventive measures are few and far between. There is a growing scientific consensus that taking low doses of aspirin early in pregnancy may prevent preeclampsia, but this therapy is not widely used and is primarily effective for women already at high risk for the disease. Women unlikely to get preeclampsia can still get the syndrome out of the blue. “Unfortunately, that is all we can offer women at this point,” Triche says.

“We want to study preeclampsia using Alzheimer’s tools. All of us in the field are trying to race to the front to combat the disease,” Sharma says. “When there is no concerted effort to pursue novel concepts, we end up ignoring some wonderful observations.”

In June 2015, Women & Infants received a nearly $5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to support its work in perinatal biology, and under Padbury and Sharma’s leadership, research into preterm birth and preeclampsia will remain strong.

“If we reconcile our ideas, we can come up with a conclusive but very powerful approach,” Sharma says. “I hope it happens sooner rather than later.”

Josey arrived home in Brooklyn on a cold and windy afternoon in March 2014. The rumble of the subway shook her apartment as she wrapped baby Liam in blankets. “I didn’t get to enjoy pregnancy,” she says. “I didn’t know how common preeclampsia was, and I didn’t know it could turn into anything else.”

Josey and her family have since moved to Far Rockaway, Queens, a neighborhood that is still feeling the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. But it’s quieter and there are fewer people around. Liam is now a healthy toddler, nearly 25 pounds and teething, and has no trouble keeping Josey up at night.

“I couldn’t be happier with how healthy he is,” Josey says. “Pregnancy was awful, but at the end of it, well, look. Here’s a little person.”