There are around 100,000 specimens of plants, fungi, algae, and the like in the Brown University Herbarium. Most were collected more than a century ago. It’s a nice—and definitive—permanent record of what used to grow in Rhode Island: “Nobody can argue with it, because we have an actual plant,” says Timothy Whitfeld, PhD, a research assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and the herbarium’s collections manager. “But what we want now is a collection from the 21st century.” Whitfeld came to Brown in 2013 with that goal in mind. “The amazing thing is that for such a small state, it has a lot of diversity,” he says. “There’s about 1,700 species that grow here.”

To properly document Rhody flora, Whitfeld has to go town by town, habitat by habitat, at least twice a year, and collect everything he can. He’s added about 1,000 specimens to the herbarium so far. “It’s very hard to get everything,” he acknowledges. But it’s important to try: a comprehensive collection is a physical record of ecological change over time and space, indispensable for botanists but also climate scientists, who can track the spread of invasive species, earlier flowerings, and fluctuations in diversity and distribution. When Whitfeld has grant money, he can hire undergrads to help with this massive undertaking (“even in a small state, one person can’t cover the whole area”); otherwise he’s on his own. He has one thing in his favor, at least: “Plants don’t run away,” he says. “They won’t fly away.”

THAT’S A PADDLIN’: In Rhode Island, “the best place for canoeing is the Wood River through Arcadia,” Whitfeld says, but “the Boundary Waters is the best place in the world.”

LOST WITHOUT IT: A handheld GPS helps Whitfeld record exactly where he finds specimens. The pink flagging helps him find the GPS on the forest floor, where it tends to blend in.

TRAILBLAZERS: Whitfeld and his team at their camp in Papua New Guinea, where he studies tropical ecology. “The field site is a long way away from everywhere,” he says. “It feels like you’re really exploring.”

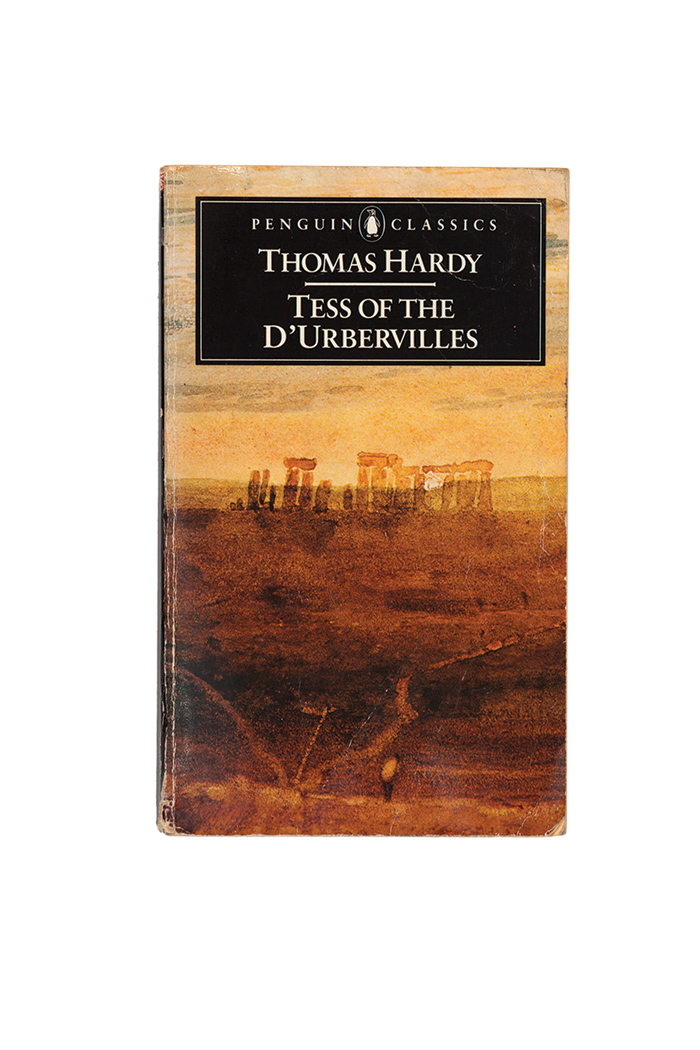

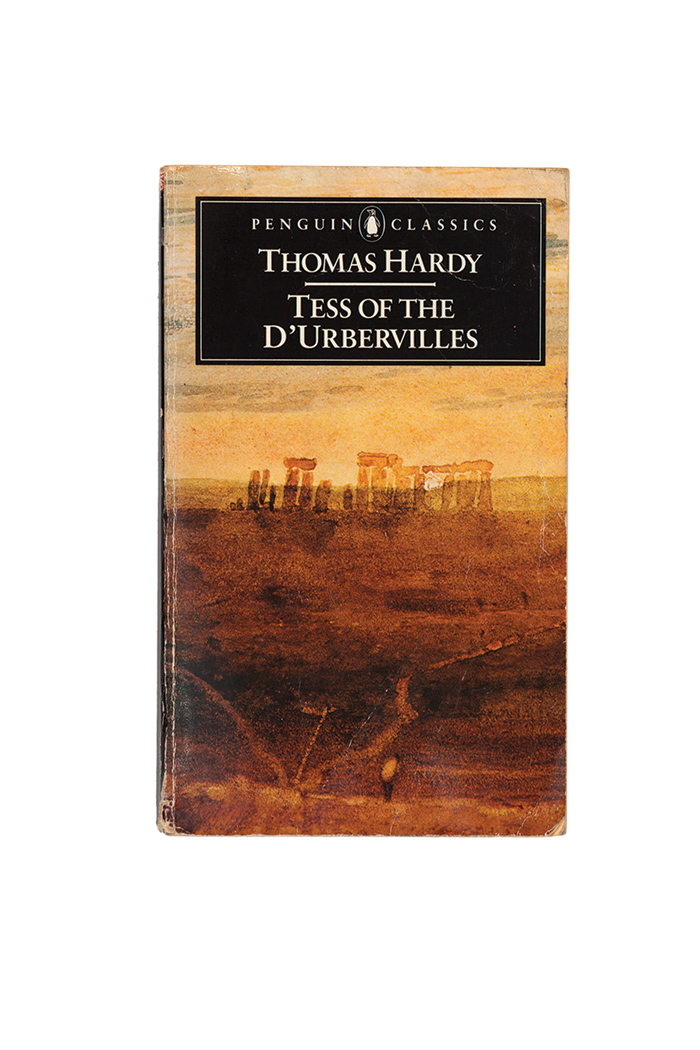

SENSE OF PLACE: Like Hardy, Whitfeld is a native of Dorset, England. The author’s vivid description of the landscape transports the expat home.

BEACHCOMBER: Ever the collector, Whitfeld likes to pick up shells at the beach, where he spends as much time as possible in the summer.

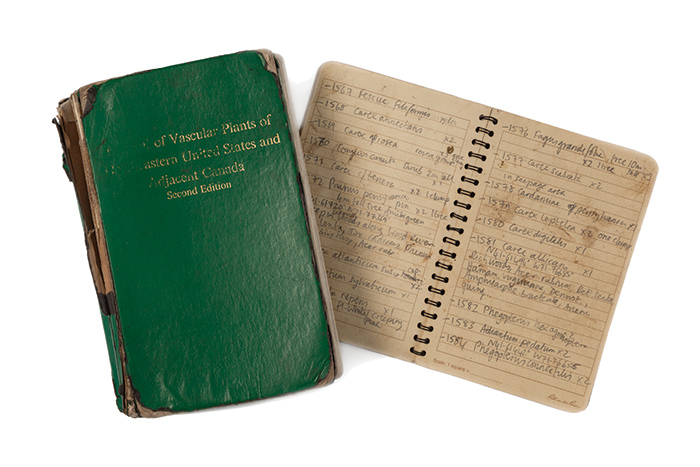

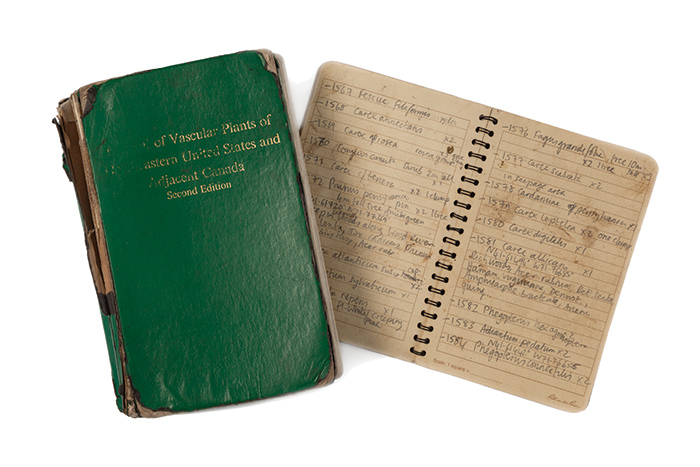

ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT: A hand lens and Whitfeld’s dog-eared field guide and notebook always accompany him into the field.

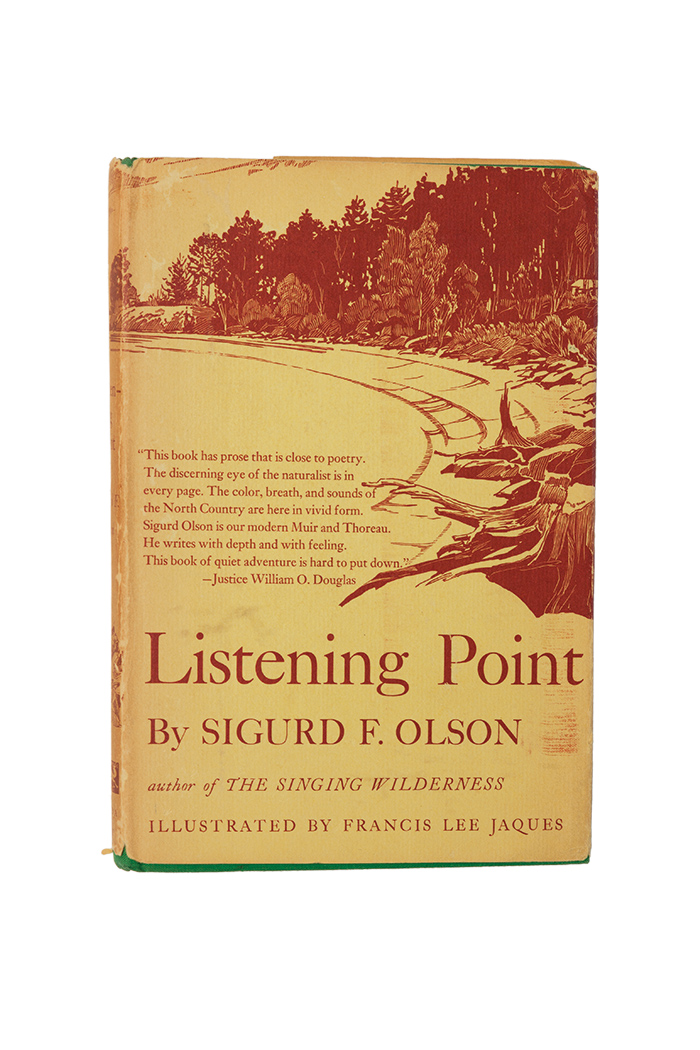

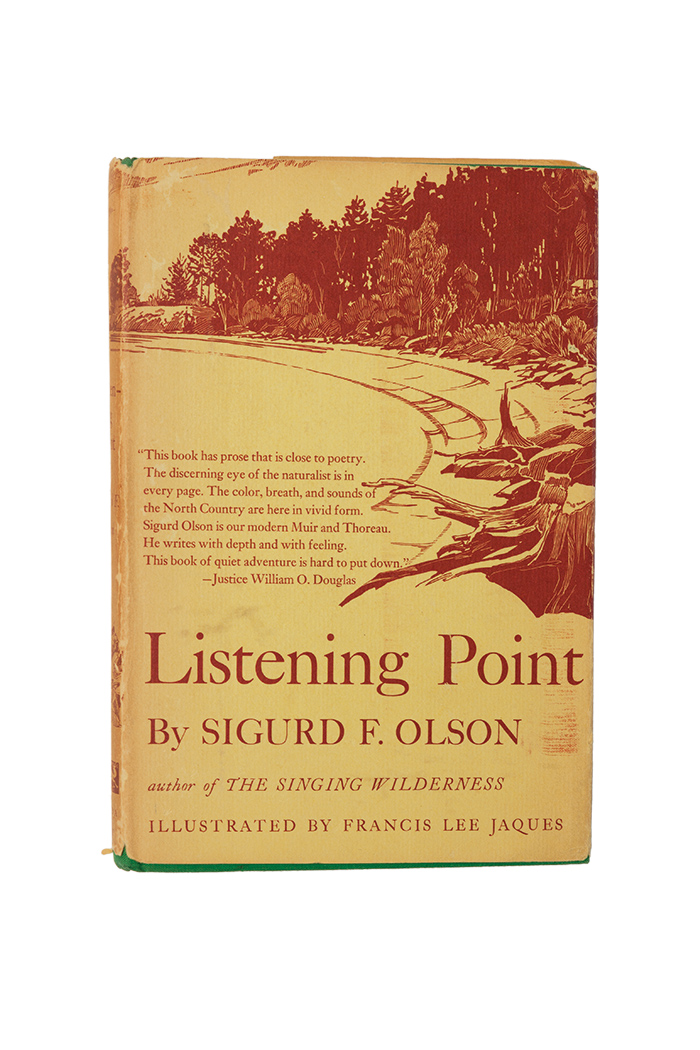

SMALL WORLD: Whitfeld, who once lived in Minnesota’s North Woods, found this first edition of Olson’s meditations on that wilderness at a shop in Johannesburg.

ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT: A hand lens and Whitfeld’s dog-eared field guide and notebook always accompany him into the field.

TRIED AND TRUE: Back in the herbarium, specimens are arranged and dried in this plant press. “It’s the same procedure that has been used for centuries,” Whitfeld says. “It’s low tech at the extreme.”

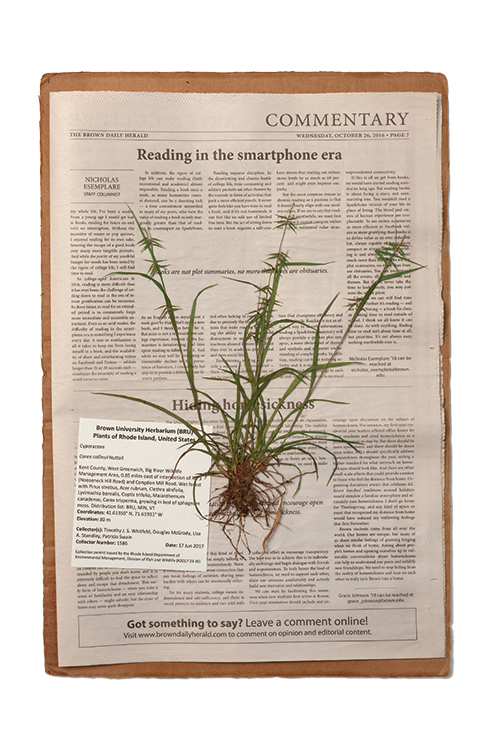

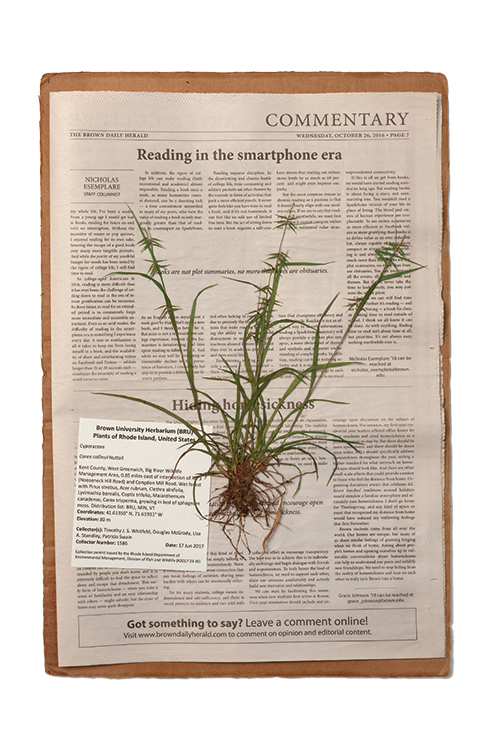

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM: In the field, Whitfeld presses collected specimens between sheets of newspaper. “The Brown Daily Herald is perfect, exactly the right size,” he says. “I hope they never stop printing the paper.”