A cadaver’s spine crippled by severe scoliosis may be a sight only an aspiring doctor could love. And it enthralled Christopher Koehler ScM’18 MD’22 when he took anatomy for the inaugural class of the Brown Gateways to Medicine, Health Care, and Research Program last year.

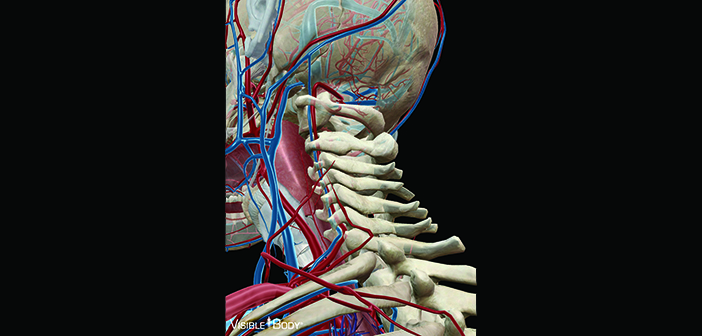

“I thought it was the coolest experience in the world,” says Koehler, now in his first year at the Warren Alpert Medical School. But Gateways—which grants a master’s degree or a certificate in medical science—also teaches anatomy digitally. A visualization app hooked up to a large screen in the anatomy lab, for example, shows students complete and idealized structures.

But, says Adam Howard ScM’18, now at the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine, “It’s very different when you’re looking at a fixed specimen than when you’re looking at a 3-D model. You try to reconcile the differences and understand what constitutes anatomic variation.”

Amy Chew, PhD, director of the Gateways anatomy course and a lecturer in ecology and evolutionary biology, has worked with apps, virtual reality programs, and even digital tables that display detailed models based on photos of a dissected cadaver. But in her 15 years of teaching anatomy she has yet to encounter a substitute for real bodies.

While the dynamic imagery offers reliable depictions of typical anatomy, “there are a lot of things that you can’t do,” says Chew, who opened

cadavers to point out structures to Gateways students.

Cadavers offer benefits beyond dissection, too, like teaching students to respect and honor the bodies themselves. Chew keeps the cadavers’ eyes covered during the course, and she introduced one as the students’ first patient.

“It’s a human body. It’s not a collection of hydrocarbon,”

Howard says. “It represents a sort of existential growth where you learn

about, simultaneously, the beauty but also the horrifying ephemerality of our lives.”