The fight against TB carries on in Ukraine.

The twins ran up to me, dressed identically in blue plaid shirts and tan shorts, excited to see a new face. They took turns counting to 17 in English, skipping numbers and laughing, eager to show off their skills to a native speaker. I asked them how long they had been in the tuberculosis hospital and they weren’t sure, but agreed it was a long time, and they were going home on Friday!

Later that day the medical team told me the 5-year-old boys had been in the hospital for more than five months. One boy was admitted and subsequently diagnosed with active tuberculosis disease, prompting his brother to be admitted and evaluated for TB. He was determined to have latent TB infection, which means his body was exposed to TB but he was not sick from it. However, he remained in the hospital with his brother for the full five months, as it was the safest place for him; their family members at home were deemed infectious or unsuitable caregivers.

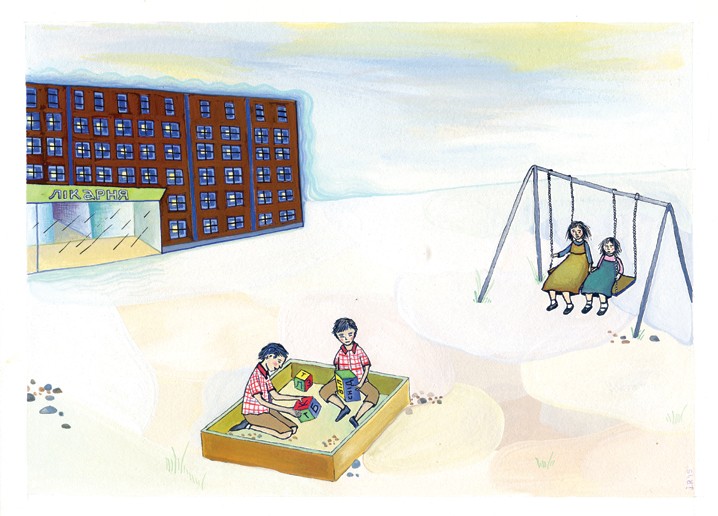

These boys were just a few of the children I met at a Ukrainian pediatric TB hospital. Other children had been there longer: one 16-year-old boy admitted 20 months earlier was finishing up a lengthy treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which he acquired from his uncle. On the playground—where the children go every day at 11 a.m. while the hospital is disinfected with ultraviolet light, tinging the halls an eerie blue—I chatted with two giggling little girls as they shared a small bench swing. One had been diagnosed with HIV and active TB after both of her parents died of those diseases; thankfully, she is doing well now.

Pediatric tuberculosis patients are a barometer for the success of a country’s TB program. Children under age 1 have about a 50-percent risk of becoming ill with active tuberculosis if exposed. They are infected with the strains around them, often from caregivers, and in Ukraine these strains may be multidrug resistant. The treatment for MDR-TB can last two years and cause severe side effects, including hearing loss. Young patients spend many critical months of normal development in a hospital, taking multiple crushed and measured pills and receiving painful injections. And this is the best of scenarios for those who have access to lifesaving anti-tuberculosis medicines.

TAKING THE HISTORY

Ukraine is geographically the largest country in Europe, and has 45 million people. It’s a country of passionate and resilient people living within a transition zone between Russia and Europe, living up to the name “Ukraina,” which is sometimes translated as “border country.” It became independent from the former Soviet Union in 1991, and since then it has struggled to maintain independence and succeed economically. Over the last two years, mismanaged government and widespread corruption fomented revolution and now war in the eastern regions with Russia. This situation, layered over a weak and crumbling health care system, has taken a significant toll on the health infrastructure of Ukraine.

Ukraine is one of the world’s highest-burden MDR-TB countries. Its antiquated Soviet health care system allows little cooperation between multiple specialized hospitals, making it impossible to navigate for many patients. TB management is very vulnerable in this setting, as it requires strict adherence to multiple drugs for a minimum of six months. When some of the drugs are not available or patients are not supported through the length of treatment, drug resistance starts to develop. MDR-TB can be very difficult and expensive to treat, sometimes costing 25 to 100 times as much as sensitive TB.

The Brown University Ukraine Collaboration, which includes Timothy Flanigan, MD, professor of medicine; Boris Skurkovich, MD, clinical professor of pediatric infectious disease; and Mariya Bachmaha MPH’16, aims to bridge research expertise in the US with colleagues in Ukraine, to improve that country’s HIV and TB clinical research capacity, in hopes it will translate to improved patient outcomes and contribute to the foundation of a new generation of researchers and caregivers.

I liken our collaboration to a snowball rolling down a hill, picking up speed and size. We have gathered a remarkable group of researchers and clinicians, such as Allyson Garcia MD’16, who was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ukraine and joined our collaboration as a first-year medical student. She is one of many Alpert medical students to have participated in projects in Ukraine through our collaboration.

There is a long road ahead, but I am certain that snowball will eventually knock out the burden of TB in Ukraine.