Their lives interrupted by war, two Ukrainian oncologists continue their work at Brown.

When Russia invaded Kyiv in 2022, the immediate priority for most people in Ukraine’s capital was the safety of their families. For many medical professionals, their second priority was care for the patients they had spent their careers serving.

Nataliia Verovkina, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Ukraine’s National Cancer Institute, had been overseeing treatment plans for patients. With military action less than five miles from her home in the suburbs, Verovkina packed up and drove across the border to safety with her husband, their son, and his grandparents. Then she and her husband, a scientific researcher, returned to Kyiv.

“I really feel a responsibility for my patients, because they were facing double stress: the war and the cancer,” Verovkina says. She and other medical professionals took turns sleeping at the hospital because it was safer and more convenient. Kyiv seemed on the verge of capture, and they weren’t sure what each new day would bring.

Meanwhile another medical oncologist, Dinara Ryspayeva, MD, PhD, who led clinical trials at an oncological hospital outside of Kyiv, had fled the country with her daughter, after a house a few doors down from hers was hit by a bomb.

They found refuge at a relative’s home in Denmark, but because of her status as a war refugee, Ryspayeva wasn’t eligible for a job in her field. She grew frustrated that she wasn’t able to use her skills, training, and knowledge to help people with cancer, and felt guilty that she was safe abroad while other medical professionals were living and working in a war zone.

“I just wanted to work at a hospital,” Ryspayeva says about her time in Denmark. “I wanted to see patients, any patients.”

That’s when she got a call from Wafik El-Deiry, MD, PhD, director of Brown’s Legorreta Cancer Center. Days after Russian troops entered Kyiv, El-Deiry had added his cancer research laboratory to a list of international labs supporting Ukrainian scientists. When he heard about Ryspayeva and Verovkina, he arranged to interview them as soon as possible.

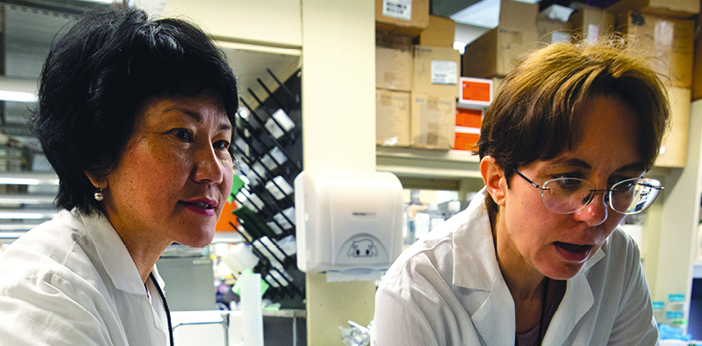

Ryspayeva says when she learned she’d gotten the job, “Really, I didn’t believe it,” she says, her voice breaking. She and Verovkina arrived at Brown last March. With support from the provost’s office, the Division of Biology and Medicine, and the Legorreta Cancer Center, both now work as assistant visiting professors at Brown, with salary and benefits.

Ryspayeva still becomes emotional when she talks about how she came to Providence. “I’m so thankful to Brown, to Dr. El-Deiry, and to the other professors who offered to bring me here.”

Verovkina acknowledges the irony of their situation. “This is because of a very sad and terrible reason,” she says, “but it is a really amazing and exceptional opportunity for us to learn.”

Although they are not licensed to practice medicine in the US, Verovkina and Ryspayeva are attending with El-Deiry, who directs the joint program in cancer biology at Brown and the Lifespan Cancer Institute. They’re also conducting research: Verovkina studies the side effects of immune blockade therapy with the goal of finding ways to minimize side effects, while Ryspayeva investigates potential breast cancer treatments.

“The unique contribution to the field of oncology in terms of innovation that physician-scientists bring is very important,” El-Deiry says. “As I’ve gotten to know Dinara and Nataliia … I’ve become impressed with their knowledge, acumen, and clinical expertise in oncology.”

Their presence here could strengthen international collaboration, he adds. “We’re trying to look at what else we can do, now that we have some Ukrainians who are anchored here who could now lead collaborations with their colleagues in Ukraine, and could also help other oncologists and physician-scientists from Ukraine who are coming here to the US,” El-Deiry says.