When crisis hits home, years of training can go to the dogs.

Cool under pressure. The best emergency physicians are cool under pressure. That was me—or so I thought.

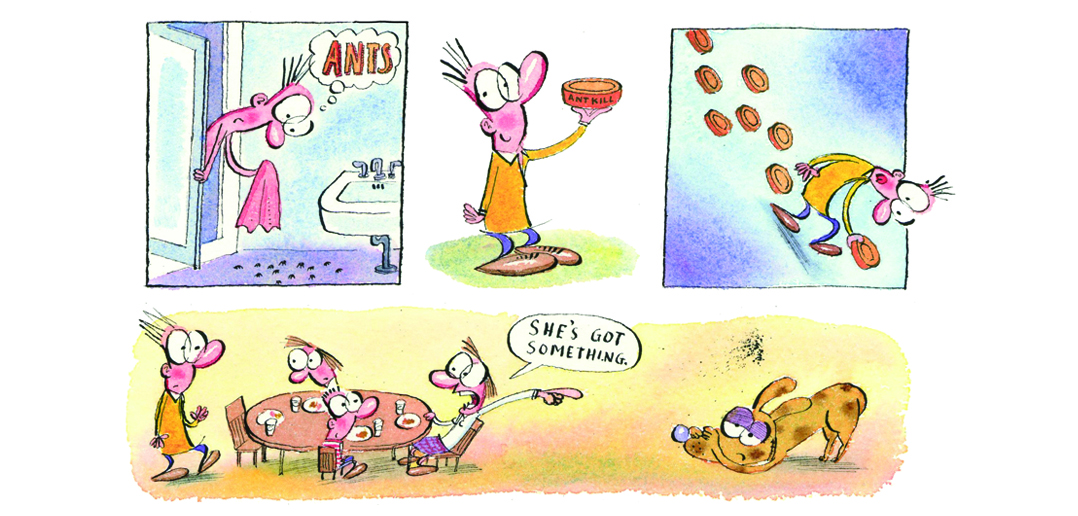

One day this past winter, while stepping out of a shower, I noticed a small cadre of ants on the bathroom floor. These were not the big black carpenter ants from the backyard that were common in summer. No. These were those tiny brown ants. There were perhaps 30 of them reconnoitering below as I toweled off.

Kill ’em. A few minutes later I had laid out two bait stations that came from a bright orange box claiming that the poison inside would “kill the queen.” Beyond question, it must have been potent stuff if it could wipe out a whole monarchy. My war against the ants was on.

The next morning, the ants were still conducting business on the bathroom floor but, apart from this, it was a usual morning. The children were reluctantly arising from their beds to get ready for school. The scent of French toast being doused by golden brown maple syrup arose from the kitchen. Lucy, our family’s new puppy, ran up the stairs to lick the faces of her two favorite companions.

The children arrived and dug into their breakfast. But Lucy, who usually joined us near the kitchen table, was sitting on the floor some 12 feet away, her head dug in between her front paws. The guilty look was unmistakable.

“She’s got something,” my wife said.

I agreed. This was not unusual for a 6-month-old goldendoodle puppy who was constantly chewing on stuff. Even with the most careful precautions, she would chew up a shoe or a sock. Occasionally one could make out a Lego piece or fragment of Tinkertoy in her feces.

Whatever she had this time, however, must have tasted really good, since she would not give it up for a doggie treat or even a piece of American cheese. Finally, Andrea grabbed her collar and pried open her mouth.

“No!” we yelled. From our tone, the kids knew immediately there was a serious problem. On the floor in front of the dog lay the mangled remnants of one of the plastic ant traps. She had ripped it wide open, revealing a white paste, which appeared to be mostly gone from the tattered surrounding black plastic casing. The label affixed to the back was torn up, wet and illegible.

“I killed my kid’s dog,” I thought to myself.

I felt vagal. It’s got to be an organophosphate. Maybe an anti-cholinergic.

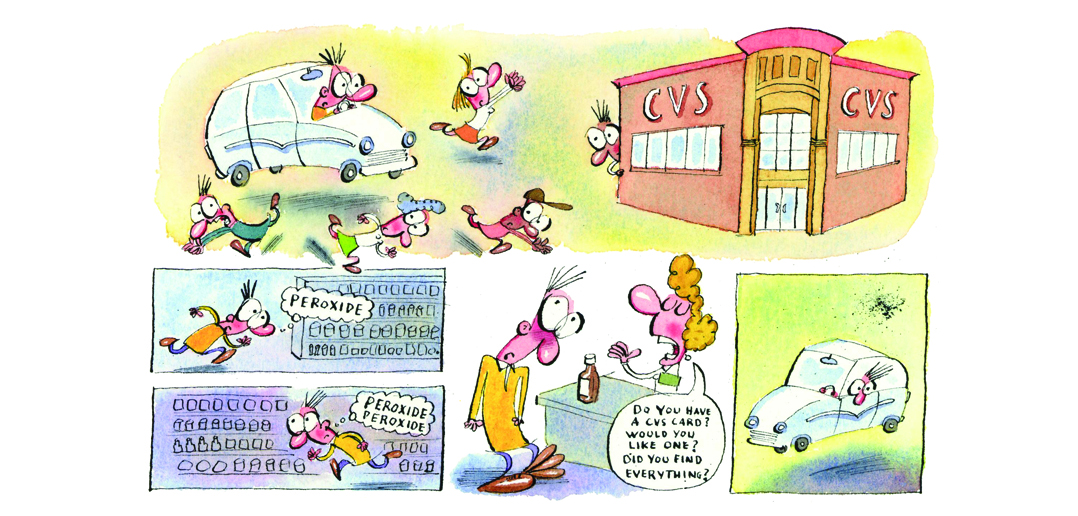

“We need peroxide—it makes them vomit!” I said to my wife. We tore through our two tackle boxes of home medical equipment: suture kits, Dermabond for the kids, some basic drugs, plaster for splinting, even a set of laryngoscopes. No peroxide. We checked the bathrooms. Nope. We are two emergency physicians—not a bottle to be had anywhere.

Several minutes later I was speeding through my residential neighborhood to the local drugstore. I can’t imagine what the neighbors were thinking as the normally docile doctor who lived up the block drove like a complete idiot while school children crossed the street. They might have thought I was trying to qualify for NASCAR in my Toyota Prius.

There is a CVS pharmacy four short blocks away. Across the parking lot, people seated near the window of Starbucks watched the unbelted driver of the speeding, gas-efficient car park haphazardly and run into the store. I knew the store well, so I found the first aid section in no time. There, I found the answer to my woes—rows of peroxide in brown bottles. I got two, just in case the first one didn’t do the job.

The checkout process seemed to take forever. Did I have a CVS card. No. Would I like to get one. No. Did I find all the items I needed? Ugh!

As I sped home I wondered, how one would get a dog to drink this stuff? Could you put it in Hershey’s syrup like we used to do with the activated charcoal in the Pedi ER?

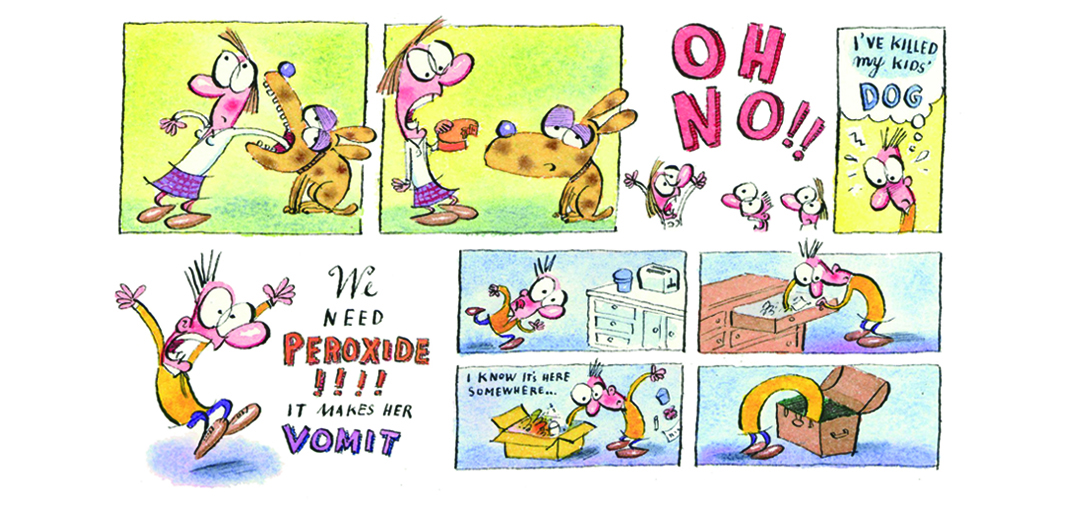

After giving my wife the peroxide I tore through the recycling to find the box for the poison.The Chameleon Law of emergency medicine states that a critical piece of equipment will blend into its surroundings exactly at the moment it is needed most. Even though the box was in the middle of the pile, I missed it. How could I call the poison center if I had no clue as to what it was? Fortunately, my wife remembered that I had put out two traps and found the remaining one. On the back was the name of the active ingredient: N-ethyl perfluoroctanesulfonamide—Organic Chemistry Gibberish.

I knew the 800 number to the regional poison center by heart—and dialed it instinctively. The voice on the other side of the phone thanked me for calling Delta Airlines. I knew that had to be a correct number! I dialed it again. It asked whether I wanted foreign or domestic travel. Damn. I booted my computer to check Micromedex. Simultaneously, I dialed the number for my own emergency department. Perhaps one of our two boarded toxicologists was on duty. At least the secretary could give me another number for the poison center. The phone rang and rang. The secretary must have been getting coffee.

After several minutes I gave up. I was able to get the number for the poison center from Google. The calm and collected poisoning consultant told me that if this ingestion had involved a small child it would be considered non- toxic. Not even an ED visit. He suggested, however, that I if needed extra reassurance, I could speak to the veterinary poisoning hotline, but that it would not be a free call. “How much?” I asked. “Sixty bucks.” I pulled my Visa from my wallet.

My wife appeared. “It’s nontoxic! I just called the vet poisoning hotline.” She had called the same number I was now dialing. It was a free call for her since she was a member of some doggie owner society or the like. It was a sulfonamide—not the carbamate, organophosphate, or anti-cholinergic I feared. It was, as best as I could tell a cousin to—dare I say—Bactrim? I started to laugh. The children rejoiced. Lucy wagged her tail.

In my own debriefing of the situation, I was embarrassed. It was an uncharacteristic moment. Driving as I did with school kids all around, tossing the seat belt aside for a few blocks, repeatedly dialing the wrong number for the poison center and insisting to myself it was correct—and doing all of this prior to even knowing what it was I was dealing with. It was contrary to all my training and practice.

Even in the most dire emergency, it is rare that the doctor does not have time to gather some basic information before “doing stuff.” And doing the wrong stuff can have disastrous consequences.

Fools rush in. And so did I the morning of the ant bait poisoning. I was not immune to fear and the bad judgment it could lead to—a hard lesson to swallow. It reminded me of a rule I read in The House of God a long time ago: “At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse.”

This story was originally published on March 8, 2016, in Littoral Medicine. Reprinted with permission.