Thousands of livers donated for transplantation are discarded or rejected every year

due to concerns about organ quality and function. But new research could greatly increase the number of livers that are transplantable, and save more lives.

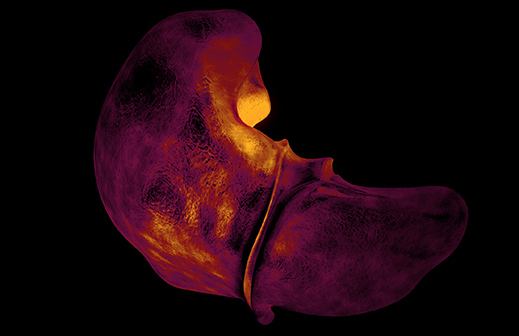

After a liver is removed from a donor’s body it undergoes perfusion, which flows blood or a blood replacement through its blood vessels to keep them open and active before transplantation surgery.

“Our new findings will allow us to design therapies that could be used during external perfusion to improve the quality of organs so that these livers can be transplanted instead of being discarded,” says Jennifer Sanders PhD’05, associate professor of pediatrics and of pathology and laboratory medicine (research). “This could potentially increase the number of transplantable livers by hundreds to thousands per year.”

For the study, which Sanders presented at the Experimental Biology 2021 meeting, the researchers perfused 12 human livers with oxygen, blood, and nutrients using an external perfusion device that mimics the human body’s circulation. They then compared livers from donors with fatty liver disease to those without. “When we examined the differences in gene expression during perfusion, we found that both types of livers had similar responses,” Sanders says. They also found that being perfused outside the body introduced injury in the livers that activated self-repair mechanisms that allowed the liver to heal and continue functioning.

The researchers are testing an experimental drug to see if it can be used during external perfusion to improve the function and quality of livers originally turned down for transplant. If the therapy is successful, they plan to begin a clinical trial to test the efficacy of the drug in a transplant setting