After private mini-concerts, hospice patients report less pain and anxiety and request fewer opioids.

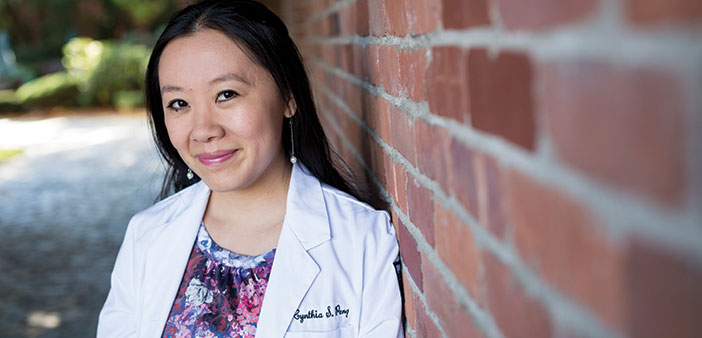

You’d expect to hear the high, melodic notes of a Mozart concerto in a grand orchestral hall, not in a small hospital room. But Cynthia Peng MD’20 thinks that shouldn’t be the case.

“[Music] should be something that everyday people can participate in,” says Peng, an accomplished flutist. “I hope more hospitals and health care settings can make music accessible as a source of comfort for patients and their families.”

In 2017, Peng designed a study to integrate music into hospital settings. She worked with Kate Lally, MD, former assistant professor of medicine and chief of palliative care and hospice medical director for Care New England; and Kelly Baxter, MS, APRN, ACHPN, Care New England’s lead palliative care nurse practitioner.

They hypothesized that music might help hospice and palliative care patients contend with pain and stress and improve their moods. Previous research has shown that patients who engage with visual arts, creative writing, and other expressive activities report improved emotional and psychological well-being, they say.

“The field of palliative care is very mindful of the patient as a whole person, looking out for their spiritual and emotional well-being in addition to their physical health,” says Peng, the lead author of the study, which was published in July in the American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Music was integrated into routine patient visits by the palliative care physician. Shortly after that interaction, Peng played for the patient and any family or friends present in the patient’s room.

“A lot of these patients are inpatient for long periods of time,” Peng says. “Having an intimate, enjoyable experience for the patients is really valuable, especially when they’re facing a lot of difficult decisions, symptom-management issues, maybe facing the end of life.”

The team tracked both patients’ opioid use and their self-reported states before and after they were treated to their private mini-concerts. Patients who opted for the music intervention filled out a six-question version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, which is designed to get a patient’s perspective on their symptoms.

“The music made me think of God, granting me peace, strength and hope,” one patient wrote. Another wrote, “I want to go home in a happy mood. I want to spend as much time as possible with my kids and grandkids as possible [sic]. I am now getting discharged in a good mood.”

Of the 46 patients in the study, 33 used opioids, and the researchers tracked their levels of use before and after the music intervention. These patients often require high doses, and although one might expect opiate use to increase after a physician visit, the authors wrote, the study gathered evidence that suggested a trend toward a decrease in opioid use.

While the study was conducted in a limited timeframe and patient census, Peng says, “To demonstrate that in this high-symptom-burden population that something non-pharmacological could influence their own usage is pretty remarkable.”

Peng and Baxter have been brainstorming ways to keep the music going even when a live musician cannot be there. They’ve curated a playlist with some of the top song requests that is accessible to anyone with an internet connection: https://soundcloud.com/musicismedicine_cne.