Lucy tells Charlie Brown to snap out of it, setting up the perfect joke—and a timely critique of psychoanalysis.

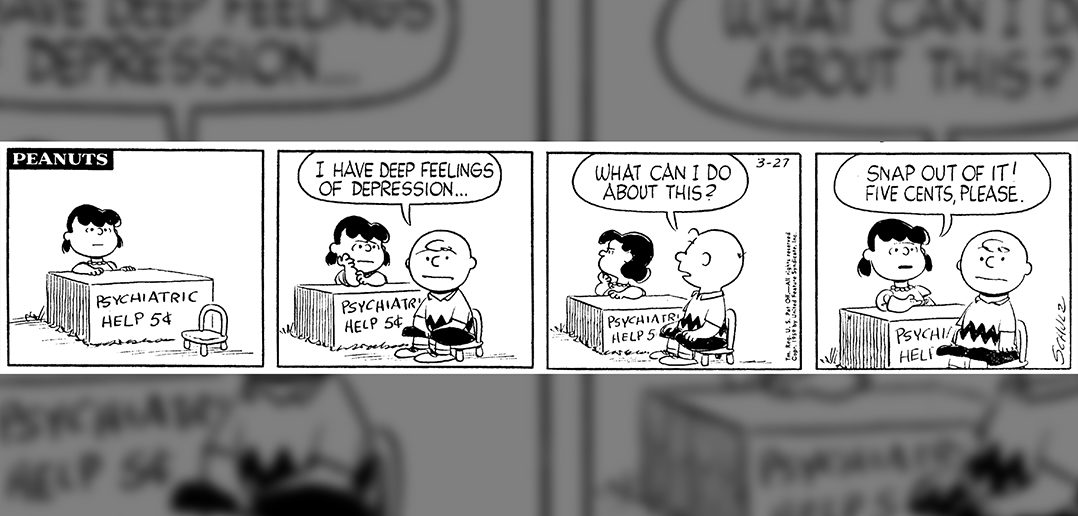

Lucy van Pelt first played psychotherapist on March 27, 1959. In the seminal strip, she sits behind a box labeled, “Psychiatric Help 5¢.” Charlie Brown takes a seat on the low chair provided for clients. “I have deep feelings of depression…” he says, and then, “What can I do about this?” Lucy puts a finger to her chin. Then she leans on folded arms and delivers her interpretation, “Snap out of it! Five cents, please.” It is a perfect joke.

Perfect jokes are meant to be built on. Charles Schulz will fiddle with this one endlessly. The consultation box will grow a signboard and a second tagline, “The Doctor is In.” Snoopy will compete with Lucy from behind a board that advertises, “Friendly advice, 2¢,” or “Hug a warm puppy, 2¢.” Lucy will use the booth for a travel agency. She will dispense valentines from the booth, and a dish called goop, also five cents. These versions are funny, when they are, because they play off the original, where Lucy offers dismissal in the guise of treatment.

Most of the series will involve psychiatric care. Lucy will tell Charlie Brown to stop his silly worrying. When he asks how, she’ll say, “That’s your worry! Five cents, please!” Charlie Brown will complain that people talk over him and go on and on. In response, Lucy will do just that. Charlie Brown will achieve the long view: “I’ve been coming to you for some time now, but I don’t really feel that I’m getting any better.” Is he any worse? No? Five cents!

The jokes gain from their constant elements. Charlie Brown feels unease. Lucy fails to provide what he’s come for. The billing is relentless. Finally, the assemblage, the theme and variations, become the work of art, a grand commentary on the impossible relationship among need, trust, help, and character.

In this way, the doctor-is-in collection parallels Schulz’s most famous running gag, the one with the football. Here, the script is more uniform. Lucy places the ball. Charlie runs toward it. While he’s in the act of kicking, she pulls it away. He should have learned his lesson, but he hasn’t. Each time, he’s wary. Each time, Lucy convinces him to rely on her despite all. The result is another pratfall.

The first football-gag cartoon involving Lucy appeared in 1952, in a Sunday strip with ten frames, enough space for her to fool Charlie Brown twice. The doubling is necessary, because the poignancy is in reiteration. The joke is about ignoring experience. The joke is about who each one is. Charlie Brown is trusting to a fault—or a virtue. He prefers to trust, however often his faith is betrayed. Giving fellow humans the benefit of the doubt is a fine if painful way to live. “Don’t! Don’t!” we cry to Charlie Brown, and then we’re glad he does.

We, too, take pratfalls. We, too, may be the better for taking them. There’s solace in that observation, and food for thought, too, about what’s right for us. If betrayal is the way of the world, how should a person live?

At first glance, the doctor gag runs on the same principle. Repeatedly, Charlie Brown exposes himself to ridicule by baring his soul. Repeatedly, Lucy brings him up short. But after that, the two jokes differ.

To understand the football joke, you don’t need to know much about football. The joke is not about football. It’s about human nature. The doctor-is-in gag is less classic, less essential, because it’s more specific. It comments on character, to be sure. But it’s also about psychotherapy. Say, “The doctor is in,” and everyone gets the reference. It’s about not just any doctor but this kind, the sort who listens attentively—or not.

For a joke to work, we need to know and expect something and then to have that expectation upset or else fulfilled in an all-too-characteristic way. To understand what’s wrong with what Charlie Brown gets, we need to know what he should get, that is, to have a prior concept of psychotherapy, how it is done. The doctor-is-in jokes comment on the relationship between psychiatrist and patient.

Schulz was inclined to throw this perspective into question. When a biographer, Rheta Grimsley Johnson, asked him about his critique of psychiatry, or (as another biographer has written) child psychology, Schulz said that he was just playing with a standard cartoon set-up, the kid with the lemonade stand.

The answer is partly plausible. Before we get to the dialogue, what’s funny about the psychiatric care booth is that its product is so different from what kids ordinarily sell for a nickel. But that is also to say that Lucy and Charlie Brown—dispensing and consuming psychotherapy—are unusual kids, wise and tuned in beyond their years, kids speaking like grown-ups. In interviews, Schulz liked to appear uncomplicated and uncalculating, but he was neither. There is something disingenuous in his ducking the conclusion that when a character offering psychiatric care hosts a character complaining about deep depressive symptoms, psychiatry is at issue. Although the presentation is compact, diverse aspects of the profession seem to be in play: therapists, therapy, and the business of psychiatry.

We have an impression of therapists. They will be empathetic, thoughtful, subtle, intuitive, slow to judge, and slow to speak—intent on throwing the questioner back on himself. That’s the setup for Lucy’s punchlines. She’s chosen the profession she’s least suited to. She has the wrong temperament.

She’s also drawing from the wrong repertory. Psychiatrists make interpretations, or they did at midcentury. “Snap out of it!” is not an interpretation. It’s like the Ring Lardner line from forty years earlier: “‘Shut up,’ he explained.” The retort is no explanation, but it is how we might, honestly and impulsively, want to answer a child (that’s the setup in the Lardner novel) who asks an embarrassing question—just as “Snap out of it!” is what we sometimes feel like saying when people entrust us with an intimate complaint.

Charlie Brown has made himself vulnerable, and he’s not getting what he has a right to expect, not getting an interpretation. All the same, he has to pay. “Five cents, please” is the second joke, about how intent psychiatrists are on billing.

In one strip, Lucy admits, shamelessly, “I’ll treat any patient who has a problem and a nickel.” In another, when Charlie Brown asks whether he will ever become mature and well-adjusted, Lucy demands payment in advance, since he won’t like the answer. Working with Snoopy, Lucy spends less time treating his anxiety—fewer cartoon frames, anyway—than collecting her fee.

This theme—cash before all—is also a hoary one. George Gershwin relied on it in his song “Freud and Jung and Adler” for the 1933 musical Pardon My English. In a repeated refrain, the doctors sing that they practice psychoanalysis because it “pays twice as well” as specialties that deal with bodily ailments. Therapists are inherently comical Luftmenschen, impractical, except on this one front. They like their fees. Lucy’s perky insistence about billing gives the five-cents-please strips their final kick.

Snap out of it! works, then, because of general expectations about what constitutes help when we’re down and specific ones about how therapists are: empathetic and delicate. Five cents, please! works because of a contrasting account of therapists, as ineffectual and venal. But I wonder whether other issues are not active as well, issues even more particular to the time, the late 1950s.

For instance, what does it mean for Charlie Brown to say that he has deep feelings of depression? That last word will sound discordant to anyone familiar with a discussion, about the proper use of antidepressants, that has been current in psychiatry in recent years. It starts with the claim that depression has changed meaning, that it used to refer to very grave conditions—mostly to the depressive phase of bipolar disorder—while lesser conditions, now lumped with depression, went under the heading of neurosis. Charlie Brown’s line suggests otherwise. In daily speech, depression, anxiety, and neurosis were all in the same territory, and almost everyone suffered from them.

A second misconception is that today we’re at a high point for psychiatric diagnosis. By this account, we have pathologized normality. Who doesn’t have anxiety, depression, or an attention deficit? But Peanuts became popular at what was arguably the true high-water mark for psychiatric diagnosis. The leading mental health survey of the 1950s was the Midtown Manhattan Study. It judged 80 percent of respondents to have a condition that might merit treatment. A New York Times Magazine piece reported that “only 18.5 per cent of those investigated were ‘free enough of emotional symptoms to be considered well.’”

That same article reviewed a study from the University of Minnesota based on exhaustive personality testing of especially healthy young men. The research produced a characterization of the “normal man.” He turned out to be a rare bird and perhaps a colorless one—“a bit dull” with “limited drives and horizons.”

The fifties was, in other words, a time of obsession with and deep ambivalence about normality. In the wake of the Second World War and then the Korean War, people longed for normality and for the chance to be normal. But the condition seemed out of reach and perhaps not fully admirable. The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit was a defining work, as a book and then a movie. Was normality possible for those who had endured war? Was normality conformity? Consumerism? Blandness?

When Charlie Brown reveals his feelings of depression—and, on other occasions, anxiety—he is saying that he is like everyone else, like most of Schulz’s readers. “My anxieties have anxieties” is a Charlie Brown line, one that became a book title for Schulz. Nor is it clear that Charlie Brown’s self-doubt is less admirable or perceptive than Lucy’s certainty. We root for Charlie Brown, we want him to have successes, but we may not wish him to be other than as he is, ill at ease.

We understand this much about Charlie Brown’s depressive symptoms automatically. They serve as a premise for humor because what he has is what we all have.

It’s in our time that depression has a darker meaning. Today, the snap-out-of-it joke might be hard to tell. We’d need to distinguish Charlie Brown’s near-universal depression from a serious disorder, one where commanding a sufferer to bootstrap it might not be funny at all.

Psychiatry was in a particular phase in the 1950s as well. The first modern psychotherapeutic medications had just been developed, but they were not in widespread use. Within the profession, orthodox psychoanalysis had spawned alternatives, but they remained outside the mainstream. Freudianism had taken the country by storm in prior decades, clinically and intellectually. Psychiatry was mostly psychotherapy, and psychotherapy was mostly psychoanalysis.

It may be hard to recall how rigid orthodoxy was. Patients came for treatment many times a week, lay on the couch, associated freely, and received in response intervals of silence interrupted by interpretations laced with references to non-intuitive concepts like transference and projection, castration anxiety and penis envy. Implicitly, this complex armature made psychotherapy an apt comic foil.

At the same time, Freudian psychology had become the standard way of viewing mental functioning. Fluency in its tropes was a requirement for making art and literature and sophisticated conversation.

When she says, “Snap out of it,” Lucy is rejecting that whole apparatus. Lucy sees the emperor in his nakedness. That’s what Schulz later said about her. “She has a way of cutting right down to the truth.”

Lucy’s way is an American way—pragmatic. I have mentioned alternative schools of therapy. America had adopted or given rise to them, treatments that were less mystical and more directive than the standard version. Alfred Adler, Franz Alexander, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan all had their adherents, doctors more attentive to social phenomena and more willing to comment on patients’ behavior.

Sullivan in particular had something of Lucy in him, or perhaps it’s the other way around. When, in therapy, a young man tried to deny that a love affair had mattered to him, Sullivan interrupted: “Nonsense, you were happy with her.” The young man had enjoyed successes in the relationship, and Sullivan did not want them lost. And Sullivan could be directive. On one occasion, Sullivan reported, he interrupted a patient to exclaim, “Merciful God! Let us consider what will follow that!” Engaging in “clumsy dramatics,” Sullivan confessed, was part of his method.

Perhaps it’s just me, but I hear echoes of Sullivan in certain Lucy vignettes. For instance: Sullivan practiced with his dogs, two cocker spaniels, in the consulting room. The story goes that once a patient, a fellow psychiatrist, protested, “I wonder what would happen if you had to choose between those dogs and me!” Sullivan said, “I could arrange a referral.” I mention the legend because of the strip where Lucy asks her beloved Schroeder, “What if I told you that you had to choose between your piano and me?” Schroeder says, “That wouldn’t be difficult.”

(Here roles are reversed, with Lucy being brought to attention. Schulz made this move regularly. On one occasion, he had Lucy allow as how, in treating Charlie Brown, she has learned about herself. Charlie delivers the punchline, “Five cents, please!” The actors change but the pattern remains: sensitivity comes at a cost.)

Again, Sullivan made a grand statement that gained some currency: “There are few things that I think are so harrowing as the occasional psychiatrist who knows a great deal about right and wrong.” Peanuts features a theme along these lines when Charlie Brown tells Lucy that he bought Linus a new blanket: “I thought I was doing the right thing.” After putting finger to chin, Lucy proclaims: “In all of mankind’s history, there has never been more damage done than by people who ‘thought they were doing the right thing.’”

Sullivan’s therapeutic posture came to be called counterprojective. The patient arrived with expectations about how authority figures act. Sullivan would behave differently. Franz Alexander’s variant of psychoanalysis operated along similar lines.

By the 1950s, alternative, more vigorous approaches to patients were very much in the air. Perhaps Schulz was making fun of them, too, so that Lucy’s sharpness—her counterprojective technique—cuts both ways, as a critique both of Freudianism and its critics.

His denials notwithstanding, Schulz seems to have been conversant with the psychotherapies of his day. Famously, he coined the phrase “security blanket,” as the demotic equivalent of the British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s “transitional object.” Schulz played contract bridge regularly with a neighbor, Fritz Van Pelt, whose family name, with the v made lowercase, had become Lucy’s. The story goes that Van Pelt had taken a psychology course that covered Winnicott. When Schulz teased Van Pelt’s daughter by hiding her special bunny, the father warned Schulz off, explaining how an object halfway between toy and parent afforded a child a sense of security. Next, Linus got his blanket.

Internal evidence, in the cartoons, reveals facility with psychotherapy. When Lucy treats Snoopy for a phobia—he has become fearful of sleeping outdoors at night—she suggests that guilt (over his inadequacies as a watchdog) may be at the root. Exploring the problem, she asks Snoopy whether he was happy at home and whether he liked his mother and father. On another occasion, she tells Linus, “The fact that you realize you need help, indicates that you are not too far gone.” There’s no way that these routines are not about psychotherapy, about psychotherapy as something funny and not a little suspect.

In practice, it was impossible to be attuned to cultural trends at midcentury without being aware of psychoanalysis, pro and con. I can say a word about my own exposure. In 1959, I was in grade school. I don’t recall reading the Peanuts strip, although it appeared in our local paper. I mostly came to Schulz later, in the Happiness Is a Warm Puppy era. (It was Lucy, in a soft moment, who spoke that line.) I was likelier to be conversant with Sullivan and Alexander. My mother had read them during World War II, when she trained as an occupational therapist. Their texts featured prominently on the family’s bookshelves.

I had been exposed to the methods. Joan Doniger, a family friend who had trained with my mother in occupational therapy, was a babysitter in my early childhood. Donny, as Joan was mostly called, went on, in 1958, to found Woodley House, one of the first psychiatric halfway houses, serving people with serious mental illness. The residents were required to be in psychoanalysis, but Donny was a counterweight. She had a good deal of Lucy in her. Donny would tell residents, “I understand that you’re hallucinating, but you need to get along with your roommate—and sweep out your room.”

Perhaps it is not coincidence that, in medical school, I sought out Leston Havens as a mentor. Les was a Sullivan scholar known for his ability to surprise patients and catapult them into new levels of honesty and openness.

Here’s a Havens moment I recall from my first psychiatry rotation. A patient enters the room, charms the trainees with offhand chatter, and begins to reminisce about his pleasant childhood. Havens reaches into his pocket, whips out a bill, and says, “Five bucks says your old man was a son-of-a-bitch.” The patient, a sociopath, gets down to business.

Later, I would study schools of family therapy that were similarly confrontational.

After training, I dropped those methods. I did not often bring a patient up short, at least not intentionally. I was concerned about patients’ fragility. Perhaps I was in rebellion as well, against the dramatic techniques that had achieved prominence by the late 1970s. My, and my generation’s, version of Snap out of it! was prescribing. We used medicines to free a patient from circular thinking so that the work of self-examination could proceed.

Considering talk therapy alone: were my patients the worse for my reticence? Perhaps. We are free to imagine that Charlie Brown gains something from Lucy’s brusque response. He is being thrown back on his own resources, with the message that they may be more substantial than he believes. Lucy as therapist, I am suggesting, does not go entirely against the grain.

That’s the genius of a perfect joke, isn’t it, to encapsulate every aspect of a complex ambivalence? “Snap out of it! Five cents, please” captures and exposes contradictory feelings, of awe and contempt, toward psychoanalysis and its alternatives.

That said, it would be wrong to reduce the doctor-is-in routine to its premises. The genius of Schulz is in coaxing transcendent results from everyday material. The subject is the human condition. The humor in that perfect strip—“Snap out of it!”—is bittersweet: we feel blue, we expose our feelings, we get a bracing dismissal, and we pay for the privilege. Life’s like that. Good grief!

Even this scope is too narrow. As his fellow cartoonist, Jules Feiffer, was known to insist, Schulz was intensely modern, aware of the absurdity of our existence and the self-referential nature of art.

Late in the Peanuts canon, Schulz contributed a highly meta strip that suggests that he was continuing to puzzle out this matter of the psychiatry stand, what it was or had been about, and how seriously its content should be taken. The cartoon’s dialogue would not be out of place as a coda to a Woody Allen movie, like that routine at the end of Annie Hall about needing the eggs.

Franklin, a new character—new in the strips and new in town—asks Lucy how the lemonade business is going. Lucy corrects him: “This is a psychiatric booth.” Puzzled, Franklin asks Lucy whether she’s a real doctor. Lucy answers the question with a question: “Was the lemonade ever any good?”

This essay originally appeared in The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life, edited by Andrew Blauner ’87. “Nonsense!” by Peter Kramer. Copyright © 2019 by Peter Kramer, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.