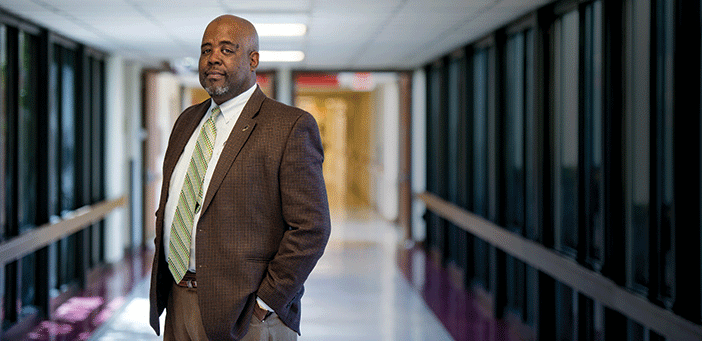

A residency alum levels the playing field.

Cedric Bright ’85 RES’93, MD, has been working in admissions nearly as long as he’s practiced medicine. During his internal medicine residency at Brown, he would help recruit residents to his program; after graduation, he was a clinical instructor and an attending at a clinic in Central Falls, and served on the undergraduate admissions committee for his alma mater.

Michele G. Cyr, MD, who was the director of the General Internal Medicine Residency Training Program at the time, says Bright was their resident recruitment “secret weapon.”

“He was so passionate,” says Cyr, now senior associate dean for academic affairs at the Warren Alpert Medical School. “It’s hard to turn Cedric down.”

Bright’s passion for admission work is more than alumni pride. He’s had remarkable success mentoring and recruiting medical students, house staff, and faculty from groups underrepresented in medicine (URM). Research has consistently shown that a more diverse health care workforce improves health outcomes for people of color.

“You have to … tell [students]repeatedly, I want you to come back, I want you to come back, I want you to be a faculty member here someday,” Bright, the new associate dean for admissions at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine, says in a phone interview. “We want to change the face of medicine. … The best way to do that is by being teachers. Each teacher has the impact to affect a student that may impact a thousand other students along the way.”

Before he went to East Carolina in February, Bright was the associate dean for inclusive excellence at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, where he earned his medical degree. More than 14 percent of UNC’s med students identify as black, compared to 7.3 percent nationwide.

He also helped the UNC Health System recruit URM residents and faculty; and he led UNC’s Medical Education Development Program, which prepares underrepresented students—including veterans and low-income and non-traditional students—for the rigors of medical and dental school. Since 1974, more than 1,300 MED Program graduates have become doctors or dentists. Bright says it’s a critical boost for students who didn’t grow up with the advantages he had.

“There’s a difference in the resources that are needed for me, a fourth-generation college student, than for somebody who is first generation,” says Bright, who with his wife, Maria, has an 11-year-old son, Andrew. “You can’t expect us to be on the same playing field when you start the game.”

Growing up in Winston-Salem with “an extraordinary support system,” Bright always knew he’d go to college and hoped he’d go to medical school. An African American surgeon at his church became a role model. “He always called me Champ. … ‘Are you doing well in school, Champ?’” Bright says. “It kept giving me the feeling, I can do anything because I’m the champ.”

Bright calls Cyr, who first encouraged him to study perceived barriers and bias in medical education, one of his “most influential mentors.” Now, Cyr says, she turns to him for advice on enhancing diversity at Brown.

“He had a huge impact on our residency and the work that we did, and the patient care we provided,” she says. “To have him go out into the world … and be so successful in diversifying institutions and the health professionals who are being educated and trained there, just makes me feel good. It doesn’t get any better than that.”