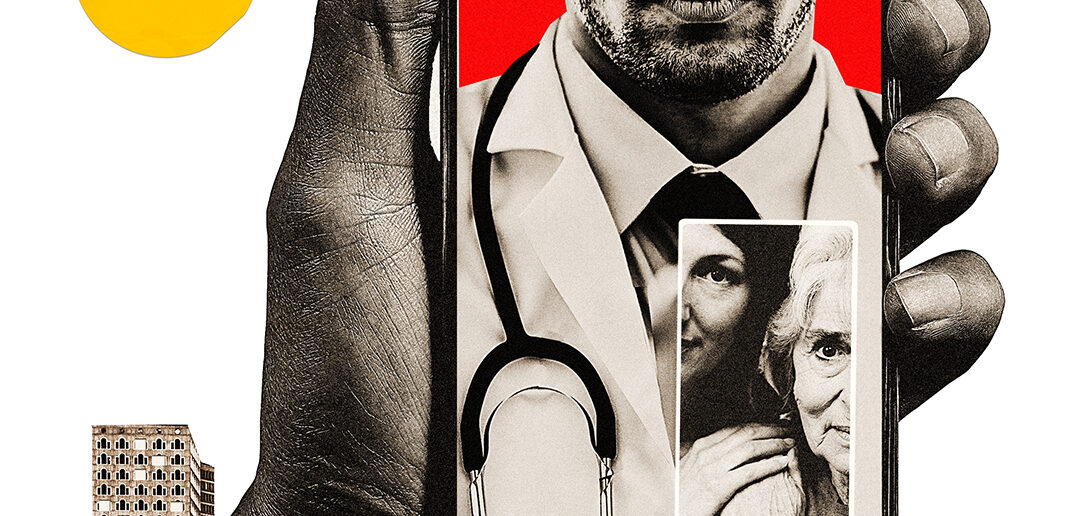

During the COVID-19 pandemic, technology has allowed patient visits to continue safely. But will its use last?

Before the pandemic, “telehealth” and “telemedicine” were buzzwords in the medical world. New technology platforms that allowed doctors to see patients via video calls were gaining ground, especially in hospitals that served rural communities where coming into an office could take hours out of someone’s day. But the technology was still mostly talked about as the next big thing with no fixed arrival date.

Then COVID-19 hit. Telemedicine took off.

“We had a lot of ideas and were wondering how and where this could be utilized. With COVID, things exploded,” says Gary Bubly, MD, professor of emergency medicine at The Warren Alpert Medical School and senior director of business development for Brown Emergency Medicine. “The timeframe to adopting telemedicine went from ‘very cautious, let’s plod along, wasn’t anybody’s priority’ to an area of pretty high priority.”

According to the Epic Health Research Network, telehealth visits increased 300 fold from March 15 to April 15, 2020, compared to the same time the year before, and telemedicine accounted for 69 percent of doctors’ visits in April.

Providers with the US Department of Veterans Affairs, which usually conducted about 10,000 telehealth appointments a week since launching their VA Video Connect platform in 2019, did 120,000 a week between February and May. Before the pandemic, Medicare beneficiaries typically did 13,000 televisits per week. In the last week of April alone, they did 1.7 million, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

It hasn’t been all smooth sailing. Technologies adopted quickly during COVID’s first peak didn’t always work well (and weren’t always HIPAA compliant). How to be reimbursed for certain services is still holding back innovative applications. And barriers to care—whether patients without broadband connections or patients who don’t own the required technology at all—are still very much in place.

But even as more doctors are seeing patients in offices again, telehealth is hanging on, and set to stay as another avenue to care.

“It’s brought back the house call,” says Yul D. Ejnes ’82 MD’85 RES’89, an associate professor of medicine and founding partner of the primary care practice Coastal Medical. Telemedicine is “going to continue in some ways, so it’s good to keep talking about it and trying to fix things that have been called out by our recent use of it.”

TRIAL AND ERROR

COVID-19 made telemedicine a necessity. Patients didn’t want to risk catching or passing the virus in doctors’ offices, and medical facilities wanted to keep their personnel safe by limiting the number of possible human-to-human interactions.

Coastal Medical went 100-percent remote in late March. Doctors, nurses, medical assistants, call center employees—they all worked virtually. “We were looking ahead and thinking about telemedicine to expand what we offered, but as far as I know, no one in the practice was using it” pre-COVID, Ejnes says. Their IT team got a telemedicine system up and running within days. “It’s the sort of thing where on our own we probably would have fumbled and scrambled before we got where we needed to be.”

The practice started with one platform and now uses three, in part for flexibility but also out of practicality: they don’t always work. “If a connection failed with one, we would try another depending what device we’re using,” Ejnes says.

During the height of the pandemic, he conducted about two-thirds of his telehealth visits through a video platform, and one-third over the phone, either because the technology didn’t work, or the patient didn’t have tools to support a video call.

Of course sometimes patients had to be seen in person. The practice kept one of their locations open for those who, after a phone or video call, needed a physical exam. That helped Coastal Medical conserve PPE and focus cleaning efforts on one building rather than across the practice.

In June they started opening offices back up, and Ejnes says that about 25 percent of his appointments are now telemedicine, which is bearing out nationally. Telehealth made up 21 percent of US doctors’ visits in July, according to the Epic Health Research Network.

EMERGENCY TELEMEDICINE

Before COVID, Brown Emergency Medicine had a peer-to-peer telehealth program for pediatric doctors, where they could conference about patients at outlying hospitals to determine whether or not to transfer them.

But aside from a program for hematology/oncology physicians to see patients who were at home in palliative care, telemedicine between doctors and patients wasn’t really on the table. “A lot of this is driven by regulations and reimbursements being impossible,” Bubly says.

That’s because telemedicine calls typically weren’t reimbursed by private insurance companies, Medicare, or Medicaid. On March 18, Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo issued an executive order that mandated reimbursement for telemedicine visits (followed by a federal executive order that made it national policy).

At the start of the crisis, medical providers used telehealth platforms to triage patients before they came through hospital doors. “Early in the pandemic, there was a relaxation of restrictions of acceptable patient-provider communication and providers quickly started using widely available video platforms like Facebook and Zoom for visits,” says Susan Duffy ’81 MD’88 F’95, PMD’20, a professor of emergency medicine and of pediatrics and co-director of telemedicine for the Department of Emergency Medicine. “While these platforms are not officially ‘HIPAA compliant,’ they are familiar, easy to access, and helped bridge the gap from in-person to virtual care.”

Brown Emergency Medicine also partnered with the City of Providence to integrate telemedicine into EMS, so emergency responders could have an emergency department physician do a video visit with the patient in the field. It had surprising results.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, the thinking was that there would be a ton of ‘worried well’ calls,” Bubly says, where someone who thought they had COVID-19 called 911 when they weren’t really sick. However, the opposite turned out to be true. “People were avoiding the ER. We found people who were sick as all heck and refusing to be transported to the hospital,” he says. Over video, physicians told people they did need to come.

Both of these applications eventually were “mothballed,” Bubly says, because the need ebbed, and no one figured out how the financial aspects would work. “Reimbursement drives everything. It’s hard paying for an emergency physician’s time if there’s no reimbursement,” he says. But he hopes that will change because it’s a potential boon for emergency response in the future.

In July, Brown Emergency Medicine launched TeleCARE, where pediatric and emergency physicians see patients virtually from noon to midnight, seven days a week, covering times when urgent care clinics are not typically open.

It works for patients because “there’s no facility charge, and you don’t need to leave your couch,” Bubly says. Doctors can see patients over the platform, order lab tests and prescribe medication, and, if necessary, work with patients’ primary care physicians on follow up, or send them to the emergency department after determining they need that level of care.

SAFER CARE FOR SENIORS

As of August, 42 percent of COVID-19 deaths had occurred in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, according to the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. The communal style of living, plus elderly patients’ susceptibility to the virus, meant limiting who came in and out of these facilities. It also meant keeping seniors at home as much as possible, whether they were in assisted care or living independently in their homes.

Telehealth helped bridge the gap. “For the first two months, we didn’t see any patients in the office. We were doing almost 100 percent telemedicine,” says Aman Nanda, MD, associate professor of medicine and a geriatrician at Rhode Island and The Miriam hospitals.

Because the elderly tend not to be internet savvy, clinicians relied on family members to set up appointments for those seniors living in their own homes, even having them take vitals with things like home blood pressure machines if available. If video wasn’t an option, doctors talked to patients over the phone.

In nursing homes, nurses became part of the telemedicine process, especially for consult visits. Instead of a cardiologist or oncologist making rounds to multiple nursing homes, the physician instead does visits virtually, with nurses examining the patients and facilitating calls. While Nanda says they are now doing 90 percent of patient visits in his office in person, virtual consults are “still going on pretty strong.”

He adds that this arrangement also is helpful for practitioners who have to quarantine after a potential exposure to the virus, or if they test positive but are asymptomatic or have a mild case. “You can still do work and see patients,” he says.

For seniors who live independently, Nanda says telehealth has allowed doctors to have a better idea of their living environment, which they wouldn’t get in an office visit. “You really see how the house and kitchen are. Are boxes left open? Is the room not clean?”—signs of cognitive impairment or decline, he says. “You may not find this in an office visit because a patient comes in well dressed and well groomed.”

If a family member is with the patient, they can give a virtual tour so the physician can see if the patient has sufficient walk space, especially if they use a walker, and then ask the family member to rearrange furniture or take up rugs if need be. “It’s not sneaky, but it just helps the doctor understand how they’re living and how we can help them and their families,” he says.

IT’S ABOUT ACCESS

Tracey Guthrie RES’99, MD, an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior and the general psychiatry residency program director at Brown, isn’t surprised that telemedicine has taken off right now. The residency program has been successfully running a telepsych program for Block Island residents for a decade (see Medicine@Brown, Fall 2019). “It’s just an excellent modality to be able to treat patients remotely,” she says.

Block Island doesn’t have a full-time psychiatrist, so to get that kind of care, residents needed to take a ferry, either pay to put their car on it or rent a car after landing, and then drive to their appointment—usually in the Providence area. “It’s a half a day or more,” Guthrie says.

In 2010, a 48-year-old Block Island resident died by suicide, which was a wakeup call that something had to change. The Block Island Mental Health Task Force (now the National Alliance on Mental Illness-Block Island, or NAMI-BI) partnered with Butler Hospital and the Brown psychiatry residency program to provide telehealth psychiatric services from a resident (who changes every year), with patients first using a room at the Harbor Baptist Church and then at the Block Island Medical Center.

During the height of COVID, they helped patients set up visits in their homes so they didn’t have to go to the medical center. “We’ve had our issues. Sometimes it didn’t work and we had to resort to phone, but I think it’s worth the struggle,” Guthrie says.

Now patients are coming into the medical center again if they so choose, doing everything from a typical visit with the Brown resident to more intensive outpatient care, all with the goal of preventing inpatient hospitalization. The program also added child and adolescent psychiatry services.

“There are already places in the country that are the future of telemedicine,” Guthrie says, like Block Island, but also Western states “where there isn’t an infrastructure of multiple hospitals and medical schools around. They have done incredible things to deal with the access issue.”

She also points to the VA, which started using telemedicine to reach veterans in states that didn’t have VA centers, or where centers were far away. When COVID struck, they hit the ground running.

Guthrie hopes that the sudden popularity of telemedicine will help Rhode Island residents in urban areas who rely on public transportation, or those who live in remote locations where driving to a doctor could take a half-hour or more each way. “Now it’s a two-hour commitment versus a one-hour commitment. That makes a difference,” she says. “It’s about access to care.”

ESTABLISHING STANDARDS OF CARE

Before COVID, the Department of Family Medicine applied for funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration for a new training initiative in telemedicine. Little did they know that by the time the $2.4 million grant was awarded, in July, the technology, and teaching students on it, would be so crucial.

“We had been wanting to do more telemedicine because we serve a patient population with geographic and transportation barriers to accessing care,” says Andrea Arena, MD, a clinical assistant professor of family medicine. “So like everyone else, once the government put in place the ability for us to conduct visits and get reimbursed from health insurance companies, we started doing this.”

The grant allows them to enhance curricular and clinical training to cultivate a workforce of primary care physicians that uses telemedicine to reach underserved populations (in rural communities far from centers of care, as well as urban communities with poor public transportation), with a specific focus on addressing the opioid epidemic.

“We’re teaching medical students from day one about telemedicine,” Arena says. On a telemedicine visit, a med student will connect with a patient over video or phone, identify themselves as a student, and do the initial part of the visit: ask questions, take a history, and so on. The preceptor then joins the call, or the student hangs up and the physician calls directly.

Arena says this experience has shown her the same barriers that a lot of her colleagues are confronting: problems with the platforms, lack of broadband access or technology to make video visits possible. However, she’s also encountered gaps between what a video can show and what happens at an in-person visit.

Of course some conditions can’t be diagnosed without a physical exam, but there are more nebulous things she feels may be lost. For example: a patient schedules an appointment for a stomachache, but “when they come in, it’s quite different. They didn’t want to disclose they were pregnant or suicidal, and I worry a little about those things that we might be missing without being there in person,” she says. Or the case when she was bantering with a patient in person who blurted out that her partner was drinking and she had to lock him out of the room every night. “Those kinds of things that can come across when you’re having a more intimate connection, one on one, face to face. I haven’t had it happen in a televisit yet,” Arena says.

There are also privacy issues. Where a teenager might have part of a visit with a parent present and part with the parent out of the room, how is that managed if the teenager is calling from the family home? What about victims of domestic violence whose partner may refuse to leave the room where the patient is calling in from?

Arena adds that in-office visits are chances to address other things, like catching up on immunizations. You can’t suggest a patient get a flu shot right then and there if they’re video chatting from a parked car—where some patients go for privacy and quiet during appointments, she says.

Despite these issues, “telehealth is definitely not going away,” she says. “I think the pandemic has made it more accessible to everyone and prompted us to be more thoughtful in our delivery of it.”