A medical student faces hard truths

To understand how we value some lives more than others, I would argue that there are few experiences more powerful than being inside a gas chamber. The space itself is rather dull and gray, nothing more than an empty room with drab concrete walls and slits in the ceiling for ventilation. But, for me, it made a world of suffering and death real and tangible. Here is where Nazism and its eugenics and racial hygiene theories manifested themselves in the mass murder of human beings. According to Nazi ideology, Jewish people unable to work were worth nothing more than the valuable commodities stolen from them and their bodies. Jews were systematically robbed, undressed, shaved, murdered, and incinerated. The Auschwitz museum displays their stolen possessions, including 40,000 shoes, suitcases with names and hometowns desperately scrawled in chalk, and piles and piles of slowly graying human hair.

Upon leaving this place of murder, I sat and reflected on the grassy knoll outside. Physically and mentally shaken, I made a solemn vow to counteract in my life and career this kind of violence. The question for me, a future physician and budding humanist, was how? I explored this question last summer as I spent two weeks in the Fellowship at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics with 11 other medical students, a neonatologist, a biomedical research ethicist, and a Holocaust historian. The fellowship seeks to educate the next generation of leaders on the role of their profession in the Holocaust through experiential learning. We toured the center of Nazi power in Berlin, held seminars in the villa where the “Final Solution” was planned, and celebrated the Sabbath with the remaining Jewish community in Krakow. As a group we discussed tough issues. What exactly did Nazi physicians do; how are their actions a part of Western medicine’s legacy; and what can we do as a profession to prevent a repeat? I learned much that troubled me.

In the 1930s, German medicine was not an abhorrent aberration but instead the peak of science. Physicians from all over the world came to Germany to study at its famous medical institutes. Highly trained German physicians, in order to advance their careers, joined the Nazi party in disproportionate numbers: 50 percent of physicians were Nazis, compared with around 15 percent of the general population; and 7 percent were in the infamous Schutzstaffel (SS), compared with 1 percent of all German citizens. The most ideological physicians then implemented Social Darwinist ideas, while the physician community did not raise its voice in condemnation. In the program nicknamed T4, a group of psychiatrists selected 70,000 Germans deemed “incurably ill” from hospitals across the country to be systematically murdered. Psychiatrists participated by staying silent and writing the transfer orders, knowing that no one ever came back. Nazi mass murder thus began with physicians.

It continued from there. The Nazi physicians then used their expertise to scale up to the mass murder of Jews and other unwanted populations. They and their support staff and nurses dispersed across Eastern Europe to set up gas chambers in the extermination camps. While there, the physicians used “valueless” humans to conduct cruel experiments, where often all the participants died. In the case of Dr. Mengele’s research at Auschwitz, a pathologist dissected the murdered corpses and sent samples of brains, hearts, eyes, and other body parts to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, to use science to prove Aryan racial superiority. Finally, it was a physician at Auschwitz who decided who should go to the work camp and who should be gassed immediately, as if the mass murder of a population were a medical decision.

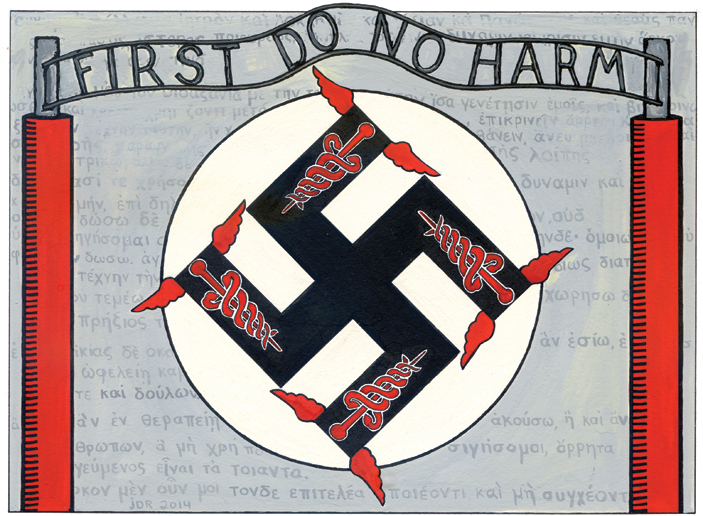

The actions of these Nazi physicians represent what scientifically trained doctors can do when our power to influence life and death loses its moral compass. Yet their crimes represent an integral period in the course of modern medicine. In reaction to their deeds and to safeguard our patients, physicians developed Institutional Review Boards to ensure ethical research and espoused individual patient autonomy as an utmost ethical concern. However, systematic devaluation of human life continues. Put simply, we value some lives more highly than others. Consider how we accept as legitimate the refusal to see patients simply because they do not have the proper insurance, or how we reimburse mental health care at lower rates. Or consider the devaluation of those living with opioid addiction— Rob Schaaf, MD, a Missouri state senator and family physician, shared this opinion after voting down a prescription drug monitoring system: “If [opioid addicts]overdose and kill themselves, it just removes them from the gene pool.”

In response to the everyday ways in which we devalue others I have devised a question that I hope will continually calibrate my moral compass. When interacting with difficult or marginalized patients, I will ask myself, “Am I treating this patient as less human than others?” If so, then I need to consciously focus on changing my thoughts and actions so as to respect the rights of all of us to be treated equally and without discrimination. This question, I believe, will help rid us of the bit of Nazism and Social Darwinism residing in all of us.