Alcohol triggers a wide range of ill effects—from poor sleep to crippling hangovers to blackouts—yet few people are thus moved to swear off drink. Are they choosing to forget that bad night or miserable next day? Or is their memory truly compromised?

Karla Kaun, PhD, thinks it might be the latter. And that could help explain the mechanisms of addiction and relapse.

“One of the things I want to understand is why drugs of abuse can produce really rewarding memories when they’re actually neurotoxins,” says Kaun, the Robert and Nancy Carney Assistant Professor of Neuroscience. “My team is trying to understand on a molecular level what drugs of abuse are doing to memories and why they’re causing cravings.”

This understanding, she adds, may someday help people recovering from addiction, perhaps by decreasing how lasting or intense those craving memories are.

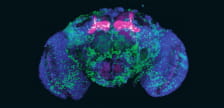

Kaun’s lab studies fruit flies, which share some key traits with humans: they have a hankering for hooch, and the molecular signals that form their reward and avoidance memories are much the same as people’s.

Last fall, the team reported in Neuron that alcohol hijacks this memory formation pathway in flies, contributing to addiction. They identified a protein that, in the presence of alcohol, triggered a molecular domino effect, subtly altering a gene that encodes another protein in neurons that recognizes dopamine.

Critically, that gene is involved in encoding whether a memory is good or bad. With one tiny change, alcohol usurped the fly’s conserved memory pathway.

“If this works the same way in humans, one glass of wine is enough to activate the pathway,” Kaun says. Something to remember the next time you crack open a bottle.