The best health care for people who are transgender is much like the best care for all people.

Doctors have had transgender patients as long as doctors have had patients—but they likely didn’t know it. Transgender, or trans, is an umbrella term for people who don’t identify with the sex they were assigned at birth, and who comprise about 0.6 percent of the US population. Yet their health care needs are disproportionately high, including high rates of psychological distress, homelessness, and physical health problems, from obesity to HIV.

These health disparities are due not only to the discrimination and rejection many transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) people face daily. Often bias and mistreatment follow them into the exam room. According to the 2015 US Transgender Survey, about one-third of respondents had at least one negative experience with a health care provider, and 23 percent didn’t seek care for fear of being mistreated. “I have an intense fear of being the patient of many of the people who I respect and work well with,” says Ry Garcia-Sampson ’12 MPH’19 MD’19, who identifies as nonbinary. “And that speaks to the level of training and education that we need to have.”

That goes for clinicians at all stages of their career, adds Professor of Pediatrics Michelle Forcier ’87, MD, MPH, a nationally recognized expert on gender and sexual health. “We still hear at times, ‘I’m not going to take care of that patient.’ … ‘I can’t get behind transgender health care,’” says Forcier, the director of the Lifespan Gender and Sexual Health Program. But the stakes of ignorance, willful or not, couldn’t be higher. “The worst outcome is not being transgender,” she says. “The worst outcome is being so invisible or stigmatized that a patient ends up being depressed, anxious, nonfunctional, or dead.”

That’s why teaching medical students to care for LGBTQ+ patients is imperative. And this year the Warren Alpert Medical School became one of the first in the country to require it, by adapting Rainbow Caduceus—which was first developed by students in 2012 as an optional, one-night training—into the Doctoring curriculum. The school also has integrated training beyond specific lessons, such as using gay and gender-diverse patients in case studies, and evaluating how students ask patients their preferred pronouns and take a sexual history in the OSCEs.

Importantly, students are hearing about trans patients outside of lectures on endocrinology or STDs. “The more that we can incorporate sexual and gender minority care into other curricula, the more it will normalize this care, and students will be able to learn about it across the boundaries of specialization,” says Alexis Drutchas RES’15, MD, a physician at Fenway Health who cofounded the Rhode Island Trans Health Conference, now in its fifth year, during her family medicine residency.

The bottom line is, trans care is patient care. Though some trans patients do seek hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery, most go to the doctor for the same reasons any patient would: a stomach bug, a flu shot, a broken arm. Anyone who can respectfully communicate with and treat a patient can help a trans patient. “It goes beyond the LGBTQ population,” Doctoring course leader Dana Chofay RES’98, MD, says. “An approach that is open-minded, nonjudgmental, pausing and listening, following your patient’s lead … regardless of the patient you’re caring for, it’s going to help you be the best doctor possible.”

ORIGIN STORY

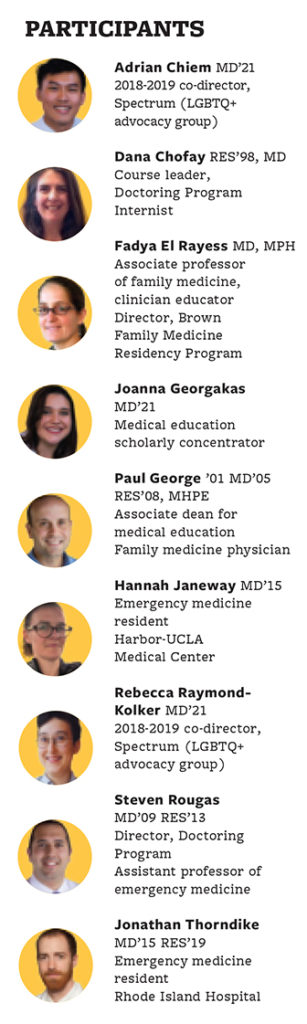

Faculty, students, and alumni talk about how Rainbow Caduceus grew from an optional, student-led training to an official part of the Doctoring curriculum. Some interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Becca Raymond-Kolker: The reason it’s called Rainbow Caduceus is at the end of the training, everyone received a Rainbow Caduceus pin to wear on their white coat.

Hannah Janeway: To be able to visually display to patients, “I’m a person who cares, is an ally, and I’m open to listening to you.” But I wanted to make sure that if people were wearing these pins, they actually were open and accepting and knew how to deal with LGBTQ patients. So we decided to design this curriculum, and if you completed the curriculum, you would get the pin. And that’s how the idea evolved.

Fadya El Rayess: Sometimes medical students are the first point of contact for patients in the health care system. By having patient-centered conversations and demonstrating openness to working with LGBTQ patients, they might make their experience in medicine better.

Jon Thorndike: Hannah did most of the brainstorming in terms of what should be part of it. And then we brought in Fadya El Rayess and a bunch of other residents and faculty to come facilitate during the session.

El Rayess: I’m not sure how I came to be that person who did it. I think any one of us could have done it. The concepts aren’t really earth-shattering. The students sent me the PowerPoint that they wanted, and I worked with them to make their goals achievable in the time frame that they had.

Janeway: We wanted it to be interactive, because a lot of times people just talk at you, and it’s not really all that helpful.

El Rayess: One activity was to have complicated conversations around helping students identify some of their implicit biases. Another exercise was to practice the language of interviewing, to practice what can be awkward conversations with each other, so that by the time they’re working with an actual patient, it’s a little more fluid.

Janeway: We mostly advertised it to first- and second-years. You usually get around 20 people, but approximately 70 people came to the first one. However the people who are going to come to these lectures are going to self-select. The goal was always that this should be a required part of the curriculum. When you’re trying to make a difference and you really believe strongly in something, it was really frustrating that that didn’t happen right away.

Paul George: Unfortunately, change is slow, but change eventually hits a tipping point, and then things happen. I was thrilled when Dr. Rougas said that he was going to include it in the Doctoring curriculum as a required component this year.

Steve Rougas: It clearly was filling a gap in our curriculum. We were able to sit down and say, how can it fit into our existing course structure? How can we make sure that it’s a high-quality program that fits with our course objectives, but also meets the needs for the entire student body? Rainbow Caduceus has been a great, stellar example of that process.

Thorndike: I think it’s a testament to Hannah Janeway’s brilliance in coordinating people and pushing the social progression forward.

Janeway: That was one hard piece of work. But another hard piece of work was setting up something that would continue to grow, and empowering people to change it and implement it in new ways. This was totally a group effort from the very beginning.

Raymond-Kolker: The generations of Spectrum have come up with this training. But it’s really been a great collaboration with the Doctoring faculty, Spectrum leadership, and Joanna Georgakas, who, as part of her scholarly concentration in Med Ed, helped take Rainbow Caduceus as an optional training that Spectrum ran and seamlessly integrate it into the Doctoring curriculum.

Joanna Georgakas: A lot of it just meant getting the right people in the room together. We already had a model to run off of. The students already like this. It’s already proven. Had that not already been a part of what people were doing at Brown, it would have been a lot harder to make that transition to being part of the formal curriculum. I thought faculty and administration buy-in was going to be the hardest part. But honestly Brown is a really special place. We don’t realize how lucky we are to have an administration that cares so much about how we feel about the curriculum.

Raymond-Kolker: We didn’t change the curriculum a ton this year. The cases stayed the same as 2017. The big difference was the speakers. Dr. Rougas and Dr. Chofay said, we need to make this more intentional, engaged learning. What I advocated strongly for was to have someone who is both a provider and can also speak to his experience of being a patient giving the keynote. Centering the voices of patients felt important to me.

Adrian Chiem: The keynote was followed up by case discussions in smaller groups, facilitated by smart facilitators who come from the community who do work with an LGBTQ population. There are so many health care providers in Providence who do really good work.

Raymond-Kolker: Dr. Rougas and Dr. Chofay also facilitated giving all of the Doctoring small group faculty a separate training. That was an ask that Spectrum had. They’re doing a great job of taking this faculty development seriously.

Chiem: At the end of the day, we have many more physicians who are coming out just a little bit more educated about these topics, which is amazing.

Dana Chofay: Obviously, the goal is training students to be the best practitioners and caregivers possible. But I always tell them that, as faculty, we’re lifelong learners. We’re always adding in new skills. The feedback that we got immediately, from students and faculty alike, was so rewarding and so validating.

Georgakas: It definitely can be improved next year. I want to make sure that it’s something that’s sustainable.

Rougas: The onus becomes on us to figure out what’s the best way to make it work, not that the student has to be the sole voice bringing these issues to light.

Chofay: Yes, absolutely. But that’s what makes our job most fulfilling, is that we are able to take these brilliant minds and nurture their passions and have a product where the community as a whole benefits from it.

Janeway: I’m just really proud of everyone who came after me. I’m sure the curriculum is even better now than it ever was. And the fact that they were able to get it to be a required curriculum—that’s amazing. Now everyone has to be exposed to it whether they want to be or not. [LAUGHTER]

CONTINUING EDUCATION

“You’re going to have a transgender patient. It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when, regardless of what specialty,” says social worker Jill Wagner, LCSW, who works with trans youth and their families at the Lifespan Adolescent Healthcare Center. Treating them doesn’t require specialized knowledge, she adds. “The hormones are kind of the easy part of care. The harder part is learning how to talk to your patients and build safety and rapport with them.”

Every provider needs “trans 101,” as Chelsea Graham RES’18 F’19, DO, puts it: “know how to use a patient’s asserted name, asserted gender, pronouns, et cetera.” Graham co-leads the gender clinic at the Family Care Center in Pawtucket, where she trains family medicine residents to care for TGD patients. That includes avoiding medical voyeurism. “People ask questions [of TGD patients]that are not related to the chief complaint,” she says. “Yes, you’re going to take a surgical history, you’re going to take a medication history. But you need to ask what’s pertinent to that patient’s care.”

Many professional societies offer webinars and other resources that are readily available to any practitioner. Several have published policy statements advocating equal access and affirmative care, including last year’s statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which was written by Jason Rafferty RES’17, MD, MPH, MEd, who treats youth in the Lifespan Gender and Sexual Health Program.

The policy statement “gives pediatric practitioners more ground to stand up and say: trans health is important. Understanding the concept of gender diversity is important. Whether you are trans or not, gender is a part of everyone’s identity that is revealed throughout development,” says Rafferty, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior. “Those messages now are more official.”

“That said,” adds Michelle Forcier ’87, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics, “policy means nothing if we don’t work hard to initiate, implement, integrate major changes in our infrastructure.” That includes electronic health records with spaces for legal and preferred name and gender identity, gender-neutral restrooms, adequate insurance coverage, and more.

“You have to have the staff on board; it can’t just be you,” adds psychiatrist Agnieszka Janicka ’05 RES’14, MD, the director of the Lifespan Adult Gender and Sexuality Behavioral Health Program. “Because the first experience that a person gets when they call is the secretary, and if that doesn’t go well, then they might not come in through the door. This is a very tight-knit population. A lot of my patients come from referrals. They don’t want to pick a provider out of the Yellow Pages.”

LGBTQ-friendly providers can get their names out through networking and listservs, like the New England Gender C.A.R.E. Consortium. But no one person can, or should, have all the answers. “We’ve really tried to emphasize the importance of teamwork and collaboration,” Rafferty says. “A lot of areas of the country, people are on their own.” But by sharing expertise, individual providers can become part of “a comprehensive and interdisciplinary system.”

Adds Fadya El Rayess, MD, MPH, director of Brown’s family medicine residency: “We are much more connected than we used to be. When we have a question about a hormone or how to interpret labs, Michelle Forcier is a text away.”

RESOURCES

■ The Fenway Institute

■ UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health

■ World Professional Association for Transgender Health

■ TGI Network of Rhode Island

■ AAMC Sexual and Gender Minority Health Resources

Providers can learn more and network at trans health and wellness conferences that take place across the country, including Rhode Island, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

‘IT’S ABOUT RESPECT’

Emily Clark of Warwick shares her experience as a trans woman and patient. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I came out three years ago. I was, I guess, on the older side of it—I was 37 when I first started transitioning. And even at that time, there still was not a lot of information, medically. I knew since I was probably 3 or 4 years old that something was off. It was a little tough to look it up in Encyclopedia Britannica back then, so I was probably in my late teens before I had any idea what I was dealing with. I just knew I felt comfortable in women’s clothing and doing more feminine things. I did get caught as a child on a couple occasions by my parents, and it didn’t go well; definitely made me feel a lot of shame.

My wife and I have been together 21 years. Six months to a year into our relationship, I told her that I like to wear women’s things. She was able to, over time, see me progress to be more comfortable in my skin and just to see me for me. So when I did eventually break down to her and say that either I need to make a change or I’m not going to live to see my next birthday, she was ready for it. She was very supportive, and she still is. I’ll tell you, the moment I came out to her, the amount of weight lifted, from just that one moment, was enormous.

I hadn’t gone to doctors previous to transition. It just wasn’t something I was comfortable with. I just didn’t care about my health. So when I decided it, that’s when I jumped online, I started doing research. I looked up doctors who dealt with gender disorder and things in that field and made sure I was going to a safe place. But I’ve heard many horror stories from other people. I was pushing my wife for years to talk to somebody, and I did finally convince her when I started transitioning. And the first doctor she saw, right in Cranston, Rhode Island, told her that I lied to her and that she should divorce me. My wife found a more understanding therapist after that.

I like that I’m hearing more doctor’s offices are introducing paperwork that will allow a patient to put their legal name, and their name and gender that they identify with. It takes away that nervousness and anxiety of having to tell the doctor, which is really good. I can tell you from personal experience that using the wrong pronoun is literally like a dagger to the heart. It truly kills you. I still remember the very first time I got ma’amed. It was at Dunkin’ Donuts. I’ll never forget it because it was such a huge deal for me.

Honestly, it’s just about respect. We don’t want somebody coming in and doing anything extra or trying too hard. Just treat us like everybody else.

A LIFE-CHANGING CAREER

Gender-affirming surgery—which alters someone’s outward appearance to more closely resemble their gender identity—is on the rise in the US. One-quarter of respondents to the 2015 US Transgender Survey said they’d had at least one procedure, such as chest reconstruction (known as top surgery), facial feminization, hysterectomy, or genital surgery (bottom surgery). The authors of a 2018 study in JAMA Surgery predicted the number of surgeries will continue to increase alongside the expansion of insurance coverage.

Not every transgender person wants to undergo surgery. Aside from the considerable expense and personal preference, some patients are deterred by the complications of certain procedures. “The biggest commitment is the female-to-male bottom surgery, because the complication rates are a lot higher,” says Daniel Kwan, MD, clinical assistant professor of surgery. “It’s a more involved surgery.”

Kwan says he was “lucky” to experience transgender care during his residency and fellowship, at the University of Chicago, but such training isn’t standard across US plastic surgery programs. As the division chief of reconstructive surgery for the Lifespan Physician Group, he says about half of his practice is gender-affirming surgeries, mostly facial feminization and top surgeries, while “vaginoplasty has been growing quite steadily.”

Plastic surgeon Alexes Hazen ’87 MD’96, P’18, has built a busy practice around transgender care. Her first trans patient, 10 years ago, was referred to her for a mastectomy and chest reconstruction. “The patient was, like, how many of these have you done? And I was, like, zero. I’ve done exactly zero,” Hazen recalls in a phone interview. “I had no education in it.” Hazen read whatever papers she could find on how to do the procedure—“fortunately, it’s not that complicated”—and gained the patient’s trust.

The surgery changed both their lives. When Hazen had to examine the patient, who had a beard and bound his chest, he was “so embarrassed and shy” he didn’t want to take his shirt off, Hazen says. It was “really, really uncomfortable.” But post-op “he’s literally lying on the hospital bed, with no shirt on,” she says. “I was like, wow. He’s that comfortable. I mean, just a different person.” She started learning everything she could, and her reputation grew in the trans community. She’s perfected her techniques, and developed new ones; she recently published her technique to create a nipple in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. A clinical associate professor of plastic surgery at NYU, Hazen also trains residents and mentors interested med students. “It’s become a very, very important part of my life.”

Urologist Geolani Dy ’08 MD’12 wanted to be an advocate for trans patients but never thought she’d get to care for them surgically. Though her residency at the University of Washington offered no surgical training in gender-affirming procedures, she did get support to seek it out elsewhere, and furthered her education in trans health and bottom surgery with a fellowship at NYU. Helping patients through the long and arduous surgical process is “gratifying,” Dy says, but she cautions that they face “challenges that surgery alone will not address. We need to be mindful of that, and think about transgender health as a holistic, lifelong continuum of care.”

Dy, who will join Oregon Health & Science University’s Transgender Health Program this summer, has found additional satisfaction as an educator. She co-created a trans health curriculum for urology residents that’s now part of the American Urological Association core curriculum. “A lot of it is just understanding what transgender and gender nonbinary are, understanding appropriate pronouns, and how to make patients feel more comfortable when seeking urologic care,” Dy says. “And then, of course, it goes into the basics of what a vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, or metoidioplasty might entail, and how to identify and manage complications.” The training meets a growing demand: as more insurers cover surgery, she says, “surgeons are recognizing that these are services that we as a community are ill-equipped to provide.”