By turning to local resources and know-how, surgeons can improve global access to care.

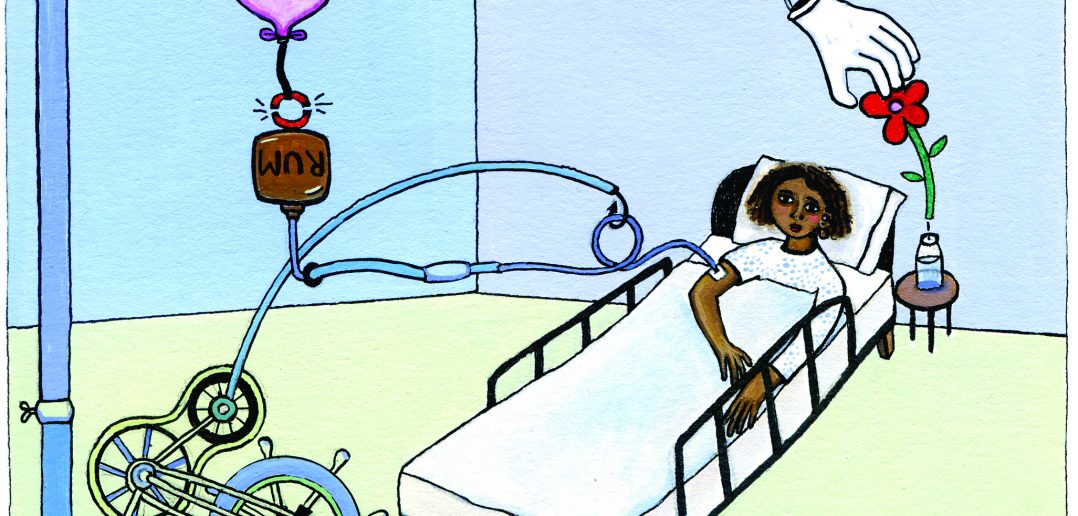

My relaxing morning on the beach came to an abrupt end when a foray into the water resulted in searing nerve pain in the tibial and peroneal distribution of my right foot. The culprit: an exotic sea creature. The place: San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua. As I applied pressure to dull the pain and stop the bleeding, some locals swung to the rescue; they knew what it was that had stung me (some relative of a stingray) and, more importantly, how to treat it. My foot was thrust into a bucket of water and a shot of rum appeared in my hand. Local resources and knowledge endemic to place saved the day.

I was in Nicaragua on Alpert Medical School’s new, monthlong surgical endoscopy elective, led by Andrew Stephen, MD, assistant professor of surgery (trauma), and Milton Mairena, MD, a general and endoscopic surgeon at Hospital SUMEDICO in Managua. For this international health rotation, a classmate and I scrubbed in on general and trauma surgeries and observed surgical endoscopies at three hospitals in the capital city of Managua: Hospital Antonio Lenin Fonseca, one of the public teaching hospitals and trauma centers with incredibly high emergent and surgical volume; Hospital SUMEDICO, which has more advanced endoscopic and laparoscopic facilities and equipment, and accepts both private and Social Security Institute (INSS) patients; and the police hospital, a center for surgical endoscopy and general surgery that serves law enforcement personnel as well as INSS patients.

A resident at Lenin Fonseca described the provision of health care in Nicaragua as an “effort to practice evidence-based medicine in low-resource settings.” I was struck time and again by the ways physicians in Nicaragua advocate for their patients to receive the care that they need, as well as their refusal to admit defeat when resources fail to materialize. Their pride, knowledge, and ingenuity are tangible and endemic resources.

In each hospital I sought to understand the limitations (and corresponding innovations) that come with practicing medicine in a setting with far fewer resources than the Rhode Island operating rooms to which I’m accustomed. The differences range from mundane frustrations to startling omissions to novel workarounds. Masks and surgical caps are often absent from the supply closets in the public hospital; endoscopies are often done without anesthesia; and it is not unheard of for a resident to go to a local hardware store to craft a negative pressure system to help with wound closure.

The care conversations during rounds resembled those we have in the States, but required some local contextualization and consideration of what to do in the absence of resources. One morning, we discussed a septic patient who had been referred after a complicated jejunostomy. She had a frozen abdomen and there was no way to surgically treat the infection; antibiotics were continued. More pressing was that she was wasting in front of us. Her care team requested TPN (total parenteral nutrition), but the IV formula often takes weeks to materialize from the government stock. A long conversation followed regarding a creative substitute to TPN, with some even offering to make it.

CALL TO ACTION

Local differences in surgical approaches and resources are finally garnering the attention of the global health field. In a 2015 article in the World Journal of Surgery, Charlie Mock, MPH PhD ’77 MD’80 RES’88, a professor of global health and of surgery at the University of Washington, highlights the importance of understanding these differences. Worldwide, he writes, upwards of 5 billion people do not have access to safe, affordable surgical and anesthesia care when needed; only 6 percent of the surgeries done each year are performed in the world’s poorest countries. Emphasis should be placed on “surgical care that addresses conditions that have very large health burdens and for which there are surgical procedures (and related care) that are highly cost effective and that are feasible to promote globally,” such as complications of pregnancy, injury, surgical emergencies, and congenital anomalies.

Mock also quotes a resolution by the World Health Assembly to strengthen emergency and essential surgical care and anesthesia. The resolution seeks to “raise awareness of cost-effective options to reduce morbidity, mortality […] through improved organization and planning of provision of anesthesia and surgical care that is appropriate for resource constrained countries,” he writes. Both the number of specialists and the surgical volume need to increase; in so doing, the perioperative mortality rate will decline. Global surgery now has an agenda.

In Nicaragua, I saw firsthand why making surgery a main focus of global health is of utmost importance. Our patients ranged from law enforcement agents needing endoscopic diagnosis of H. pylori, to people with end-stage pancreatic cancer seeking surgical intervention or hospice care in the private sector, to shooting and stabbing victims who had no insurance or ability to pay. In each instance, and to varying degrees, physicians asked: what OR or endoscopic suite space is available? What personnel are in place to perform the surgery? Are there enough anesthesiologists? What anesthetic medications are available? We rarely have to ask these questions in Rhode Island; we take for granted that these basic surgical needs are met and care conversations proceed from there. In an increasingly globalized world, and with calls for greater global equity in surgical care, surgical training and practice must consider the nuances of time and place.

But awareness isn’t enough. Mock writes that, unless physicians respond to the global call to action to increase access to surgical care, all of the studies are at “risk of becoming academic exercises and wasted effort.” My background in medical anthropology and qualitative research teaches me that individual stories speak volumes and inform statistics. My clinical training illustrates the breadth and depth of potential that physicians have to enhance standards of existence. As I figure out my path in medicine, of one thing I am sure: I have the obligation and privilege to take the stories I have heard and translate my knowledge into action. Be it as a surgeon in the OR, an emergency physician working to stabilize and triage patients from the field, or an internist managing patients with a surgical history, I will combine this call to action with local resources and knowledge endemic to place to help these academic exercises impact global health.