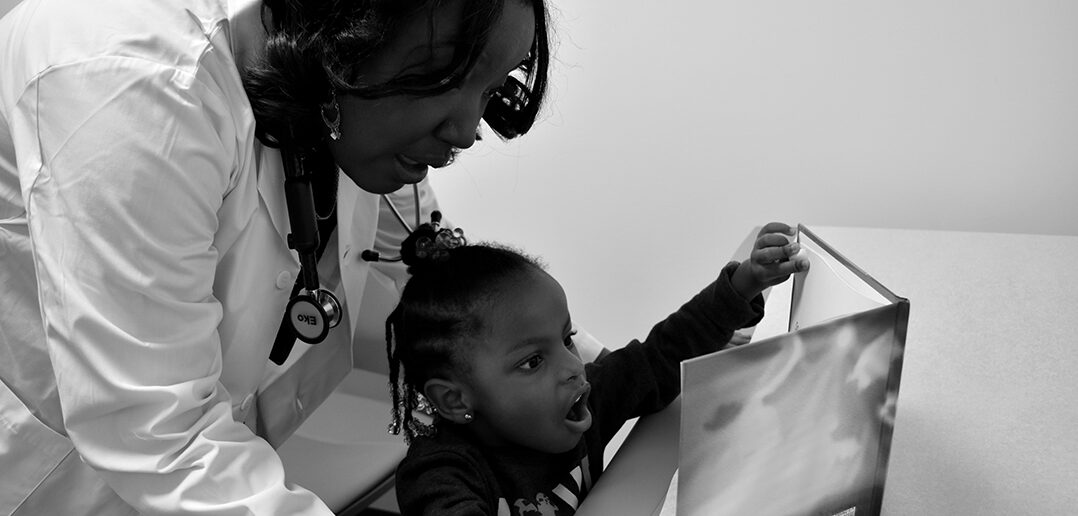

Alumna Suzette Brown is embedding doctors’ offices in community organizations to ease access to health care and social services.

The video call is grainy and a little shaky. Only Suzette Brown’s eyes are visible above her surgical mask. “Sorry,” she says, grappling with the phone. “I’m seeing patients today.”

“Well, we called to make your day a little better,” a man says. “We wanted to tell you that you’re one of the five winners of The David Prize.”

The caller is Jed Walentas, and The David Prize is a no-strings-attached cash award named for his father, real estate mogul David Walentas. Awarded for the first time in 2020, the prize provided $200,000 each to five New Yorkers who have a vision to improve life in the five boroughs.

Brown ’00 MD’07, MPH, was one of 6,500 applicants and her award will support Strong Children Wellness, a pediatrics practice that she cofounded. Born in Brooklyn, she spent her early childhood there before moving to Long Island and then attending Brown. After completing her medical training, she returned to New York to work with underserved populations.

Medicine@Brown talked to Brown about the realities of caring for children and families and how The David Prize will help her change their lives.

What was your experience at Brown like?

I went to Brown for undergrad, graduated in 2000, majored in community health, and thought for a time that I wanted to do global health. I got a master’s in public health at Yale and spent some time doing pediatric HIV work in South Africa. I decided I wanted to go to medical school because I felt that the training and expertise would position me to do more around clinical service delivery than just having a solely public health background would. I applied through the Brown Avenue [route of admission]and finished up in 2007.

While I was at Brown, I continued to do a lot of global health work in South Africa focused on HIV treatment adherence. My mentor, David Pugatch [F’97, MD], was a pediatric infectious disease doc at Brown and worked with me on a number of projects. And for a time, I thought I wanted to pursue infectious disease and HIV work.

After Brown, I matched at Duke for [pediatrics]residency and went down to North Carolina. I cared for many low-income families and saw that there were a ton of issues that kids and families were facing in our own backyard that needed to be addressed. I realized that I didn’t necessarily have to go overseas to address the issues around health equity and access that I was most passionate about. I gradually moved away from pediatric infectious disease and global health and decided I wanted to focus on helping marginalized families locally who were facing adversity and toxic stress that was impeding their ability to achieve good health outcomes.

This was before social determinants of health was a hot topic that everyone was focusing on. I didn’t really have too much support when I was in residency around doing this work, because nobody really got it. They didn’t know how to help move it forward. I just did my own thing and got grant funding to focus on a sub-population of high-risk kids in foster care and in group homes and figure out how to improve care continuity for that population.

From there you went to Harvard. What did you do there?

I ended up doing a fellowship that Harvard offered physicians interested in doing health services research and thinking about systems changes—it pushed me to think differently and more expansively about health systems and health care delivery. I still focused my research on the foster care population and on trying to figure out how to better serve that population and address their mental health needs in a way that was more effective and that helped foster parents better manage their kids’ behavioral problems.

After fellowship, I landed at Maimonides in Brooklyn, NY, and did a combination of clinical care and research. It was really there that I realized how broken and limited primary care was for a lot of families. I was caring for families who were contending with a lot of adversity and toxic stress … homelessness, domestic violence, substance abuse, parental mental illness, parental incarceration, lots of kids with behavioral health needs, in addition to kids who had chronic health conditions and comorbid mental health issues.

Trying to figure out how to help families navigate all of these issues was challenging. And the health system just wasn’t supporting them in a holistic way to help them address their many needs. What I ended up doing was forging partnerships with community organizations that had expertise addressing certain social needs. I had also gotten some funding to integrate mental health services into primary care. The goal was always to try to create this wraparound system of social services and mental health services that patients could access within primary care. But I was faced with so many roadblocks along the way.

Like what?

The health systems just weren’t interested in creating that. It was just like, “OK, you need to meet certain numbers, see a certain number of patients.” And that’s the priority. They essentially said, “Yeah, integrating mental health is great, but you don’t need to really push it much farther than that.”

After a while, I just got frustrated with those limitations. And my twin sister, Nicole, who is also a Brown alum and a pediatrician—she and I graduated from Brown undergrad in 2000—

Wait, you have a twin?

Yes, she went off to Stanford for med school and I stayed at Brown. She was working at Montefiore in the Bronx as a pediatrician at the same time I was in Brooklyn at Maimonides. We were comparing notes and ranting about the same challenges and limitations. We had a third colleague, Dr. Omolara Uwemedimo, who was a pediatrician at Northwell, who we’ve known for a number of years, and she was dealing with the same limitations and frustrations but had successfully forged incredible community partnerships as well.

And a great idea was born?

We all just felt, what if we joined forces and created this dream practice that leveraged the services and expertise of community-based organizations so that our patients could easily access those services, while also being able to access comprehensive primary care? It just made sense.

I had forged partnerships with certain community-based organizations. Nicole had forged partnerships. Omolara had forged partnerships. We ended up approaching those organizations with this idea of bringing primary care to them and basically integrating a primary care practice into their organizations so that patients could get their health needs met while also having access to all of the great behavioral health and social services that the organization offered. It would be like a one-stop shop, and really help to break down the silos and the fragmentation in care that a lot of patients and families experience.

The organizations were on board. Two of them in particular—the Child Center of New York, which is a large multiservice organization in Queens, and JCCA, which is a large organization that serves kids in foster care and kids involved in the child welfare system in Brooklyn—were really excited about the idea of bringing primary care in.

We called this model of care “reverse integration” because we thought of flipping traditional integrated care on its head. We’re bringing primary care into community-based organizations rather than trying to do it the other way around, which is when services come into primary care and there are so many barriers there.

This was all in 2019-2020, right?

Right. We launched our first primary care hub location at the Child Center of New York in Queens that opened up in early August. We’ve been serving clients from the surrounding community as well as Child Center of New York clients in a very collaborative way. We really collaborate with the community partner to make sure that families are engaging in services and that they’re getting their needs met. We have meetings at least twice a month with our community partner to identify any issues and talk through how we can all best help support that family.

So you make sure no one’s falling through the cracks along the way?

Exactly. I think that kind of bidirectional communication and collaborative care between health care providers and community entities is missing a lot of times and doesn’t really happen in the robust way that it should. We’ve been working to refine a clear way of conducting collaborative care that’s really impactful for families. We’ve actually done a pretty good job doing that. It’s one thing we hope to scale and teach others how to do in the near future.

Are you physically located at the community organization?

Yes, we’re embedded in there. We have a couple of examination rooms. We share a waiting area. We’re right in the center of that organization’s site. Families can literally walk down the hall to get mental health services, walk a little bit further down the hall to get public benefits assistance, walk down another hall for GED classes and help with employment. Literally everything is on site. It mitigates the back and forth and having to navigate multiple systems to get help.

Making those connections and doing that follow-up work—do people underestimate how difficult that is for families who are facing challenges?

Absolutely. A lot of times, the family is headed by a single mom who has to work and has to figure out how to feed her kids and keep them clothed and housed and deal with their kids’ school—they have so many competing demands. Telling them, “Go call this organization to make an appointment to get help with your SNAP benefits, to get food from this food pantry,” it becomes overwhelming when you’re already dealing with so much. As clinicians, we are trying to help by giving them information on community resources, but if the burden is placed solely on them to follow up, we often end up unknowingly adding more stress. Families end up not engaging in the services that they’re referred to because they often just don’t have the time and the wherewithal to engage. Meeting them literally where they are, which is in your office, and having the ability to help them easily access what they may need within the same office setting, is critical.

How will The David Prize money help you do this?

We recently hired a family navigator. That individual helps to ensure that families connect to services, that they actually engage in services, and that they’re benefiting from the services. They’re kind of like a point person for the family and help troubleshoot, help make appointments, help get them transportation, and just really help them navigate all of the barriers that often prevent them from accessing care and other sources of help. The navigator also helps to facilitate bidirectional communication between providers in our practice and our current community partners that we’re working with, as well as any external partners that we end up working with. That person came on board in November.

One of the things that I think is also a little bit unique with our practice is that we try to leverage technology to improve access to care and engagement in care. We use a HIPAA-compliant text messaging platform to communicate with patients prior to and in between visits. We also use a patient registration and screening platform that allows patients to register for their appointment as well as complete social determinants of health screening and mental health screening on their mobile device, so we can do that prior to the appointment.

Our technology also allows parents to complete developmental screening on their mobile device for their young kids. By doing that, we’re able to get all of this information before the visit and create a little bit of a picture of who this family is, what their needs may be, and be able to prepare for that visit in a more effective way. Technology is really important to what we’re doing and The David Prize is going to help augment that and help us build out some of these technology platforms.

Would you say that this technology makes it possible to accomplish so much more in one visit?

Absolutely, that was our goal. Prior to doing this, we were limited to usually 15 to 20 minutes max [per visit]and didn’t have the time to delve deep and get a full understanding of the issues that the family and the child were facing. There was a lot of “come back, come back, come back next time” because you have no time. And, unfortunately, the family can’t always come back.

What else do you hope to get from The David Prize exposure?

In addition to the funding, The David Prize definitely tries to work with finalists and winners to connect them to folks that they think could help amplify and advance their work. We are really trying to get something called a value-based payment, or VBP, with health plans that would allow us to build out our team and provide the kind of truly comprehensive and collaborative, holistic care that we want for medically and psychosocially complex families. A VBP contract would … help to move us away from focusing on volume and help us focus on just providing quality care that is impactful for families and improves outcomes. The prize is really intentional about helping us think through that and helping us connect with the key players and stakeholders that we need to move us closer to achieving that.

We envision that this will scale beyond New York and that it has the potential to scale nationally. We can shift the paradigm when it comes to pediatric care and how you deliver services to families through this kind of reverse integration model.

What’s next for Strong Children Wellness?

I’m always looking for opportunities to partner with other community organizations and other folks doing great work on behalf of kids and families. I spend a lot of time outreaching to potential community partners. It’s been keeping us pretty busy. I’ve had the opportunity to talk to a few Brown alums since launching this. A lot of folks doing great work on behalf of kids and families and marginalized communities, especially in and around New York City, happened to go to Brown.

Our goal is to join forces with visionaries focused on empowering families and collectively being this incredible force for change. We shouldn’t continue to work in silos—we should strive to work collaboratively to have a real impact on families’ wellbeing and to help kids truly thrive.