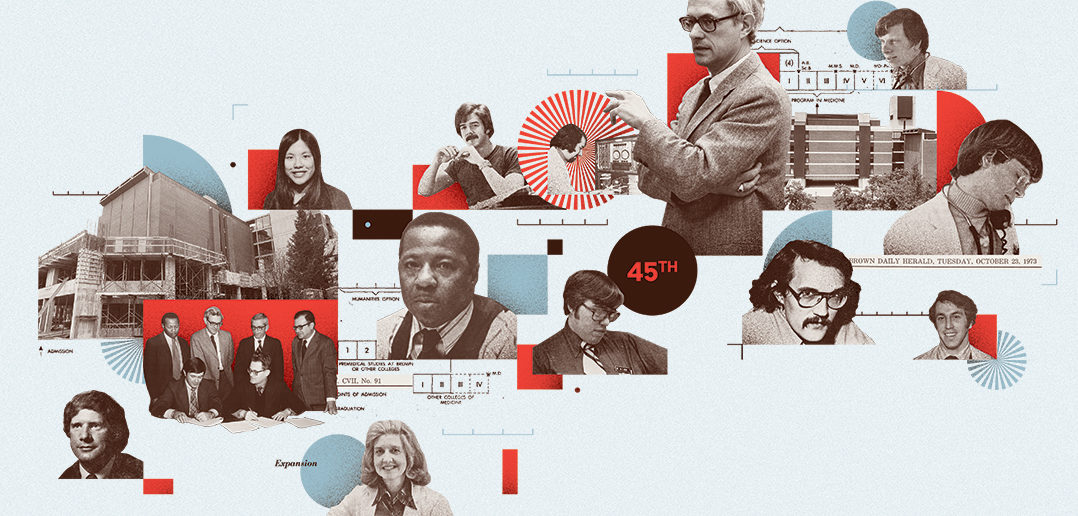

This year, the first graduating class of Brown’s modern medical school will mark its 45th anniversary. In honor of this milestone, we take a look back at how it came to be.

1962 Brown’s Board of Fellows approves the creation of a program in medical education. In the face of resistance by many faculty members to establishing any professional school that would detract from Brown’s undergraduate teaching mission, and in the absence of the critical mass of public and foundation funding a four-year medical school would require, the University is empowered by the board to begin a two-year medical program.

1963 Brown President Barnaby Keeney announces at the Rhode Island Hospital Centennial Convocation Banquet that the University will inaugurate a Special Program in the Basic Medical Sciences offering the first two years of graduate basic science education. “Our society,” he says, “has two great medical needs. One is for more people to apply the new medical science and the other for more and better people to discover the basic knowledge and find ways of applying it. Our program will help a little in the first, but it is directed primarily toward the second need for medical scientists, teachers, and clinicians who will use the research that they themselves have conducted.” The new program, initiated with funding from the Kellogg Foundation, is a six-year continuum—four years of undergraduate liberal arts education, in humanities as well as sciences, followed by two years of academic medicine, leading to a Master of Medical Science degree. Graduates are expected to pursue careers in science or go on to four-year medical schools to complete the clinical portion of their training. All the students who receive MMSc degrees during the duration of the program, between 1969 and 1972, choose to continue their studies at medical schools.

“At this point in time,” explained Stanley Aronson, who would become the first dean of the medical school at Brown, “industry in the state wanted a medical school. The critically ill had to be sent out of state. Because there were no tertiary care facilities in Rhode Island, it was difficult to recruit specialists and research physicians. The absence of a medical school affiliation meant fewer research dollars, and insurance payments collected in the state were migrating to Connecticut or Boston, which was very costly to Rhode Island government and business.” He went on to say that although in the 1960s and early ’70s, there was no great stream of federal research funding coming into the state, it was understood early on that research dollars would have downstream effects on the Rhode Island economy. “While businesses were not offering to support big building projects for the medical school just then, they did see the potential and got behind it,” Aronson said.

1964 The Biomedical Research Laboratory, a four-story structure linking Arnold Lab (1915) and the Metcalf Research Lab (1938), is built to accommodate research by faculty and students involved in the new six-year Program in the Medical Sciences.

1965 Brown’s Division of Medical Science is replaced by the newly formed Division of Biological and Medical Sciences, administered by an Executive Council led by Professor Paul F. Fenton, a cancer researcher whose work included investigating the role of obesity as a factor in disease. Professor Mac V. Edds is tapped to lead the medical component of the new entity; he is appointed director of medicine, and Professor Herman B. Chace is named director of biology.

1966 Brown President-elect Ray Lorenzo Heffner wholeheartedly endorses the University’s new medical program in his address to students and faculty at convocation. Heffner will make good on his promises to support medical education, involve students in decision-making, and keep his door open to all members of the University community, but his tenure was short; he resigned after three years as president.

1968 Pierre Galletti, who joined the Brown faculty as professor of medical science in 1967, is appointed chair of the newly formed Division of Biology and Medicine. Author of the first comprehensive book on the principles and techniques of heart-lung bypass, the standard work in the field, Galletti was internationally renowned. During his career at Brown, he will not only assist at the birth of the medical school and shepherd it through its first two decades, but he will continue to break new ground in research in physiology and biophysics and help establish Brown as a center for biomedical engineering and translational research.

1969 The first cohort of students to complete the six-year Special Program in Basic Medical Sciences graduates from Brown. They are awarded Master of Medical Science degrees; all will continue their studies at medical schools, with many going on to Harvard.

On May 20, Brown and five partner hospitals—Rhode Island Hospital, Roger Williams General Hospital, The Miriam Hospital, Providence Lying-In Hospital, and Memorial Hospital—sign an agreement of affiliation, laying the groundwork for an unprecedented collaboration in medical education in the state. Two years later, Butler Hospital will sign on to the agreement, followed in a few years by the Veterans Administration Hospital.

In October, Brown dedicates its new Biomedical Building with a celebration that includes an address by the biochemist and prolific author of science fiction and popular science books Isaac Asimov. The new building incorporates a four-story tower of labs for research in biology and medicine, two underground levels of teaching and lab spaces, and an extensive animal-care facility.

At the invitation of the Brown administration, Stanley Aronson joins the faculty as professor of medical science and joins the staff of The Miriam Hospital as pathologist-in-chief and director of laboratories. He will collaborate with Brown Provost Merton Stoltz to lay the groundwork for a prospective four-year medical school. Aronson will later say of his work with Stoltz, “We had to begin cautiously and quietly because the idea of the school was opposed by most of the faculty; many thought of it as a trade school that would diminish the academic merit of the University.”

1970 Former Professor of Chemistry Donald F. Hornig returns to Brown to take on the presidency of the University; the establishment of the four-year MD-granting medical program will be accomplished during his administration. He had been among the scientists who developed the atomic bomb at Los Alamos and would go on to serve four presidents as a science adviser. On his inauguration as president of Brown, he says, presciently: “If the private university is to continue as an important social and intellectual force, it must remain firmly in the storm center. It may mean controversy and conflict, and it may mean discomfort and dissent. Frontiers are dangerous places. The front edge of change is dangerously sharp. But it is where a great university belongs.”

1972 The Brown Corporation authorizes the establishment of a full four-year Doctor of Medicine degree program in the Division of Biology and Medicine, and the University begins planning for a full-scale medical curriculum. Pierre Galletti is appointed vice president and chief operating officer for the division, a position he will hold until 1991. Prominent among his many contributions as head of the division will be his work as a prime mover in the founding of the medical school, in the genesis of its affiliations with partner hospitals, in the development of the eight-year Program in Liberal Medical Education (in 1985), and in the expansion of biomedical research at Brown and its affiliated hospitals.

The University announces a campaign to raise $20 million for the medical program by 1980, $6 million of which will be sought from government sources. To win faculty acceptance of the four-year program in 1969, its proponents, among them Professor of Surgery Henry T. Randall, had to agree to an annual allocation of $300,000 in University funds. “That was all,” Randall said. “Beyond that, the school was on its own. [But] we never used a cent of the $300,000. Senator Claiborne Pell put in the Pell Amendment to give a capitation of $1,500 a year for medical students; with that and research grants we managed to put the school together and banked the $300,000 a year” to build up an endowment.

1974 In its first full year of existence, the clinical clerkship training program engages the Charter Twelve and 48 additional medical students in hands-on experience of the practice of medicine. The program is a landmark effort, built upon collaborations of unprecedented depth and scale between Brown and its partner physicians and hospitals. “The members of the original class, all of whom came from Brown at that point, should be counted among the founders of the medical school,” Aronson said. “It was such a crucial chemistry; we were building the school together. We had labs and a few conference rooms in the Biomedical Building, but no classrooms. So we used a room in the sub-basement for our classes. Room B-12. The students decorated it, put rugs on the walls as well as the floor, hung empty window frames and pasted seasonal pictures behind them. They were wondrous people who did great things. We told them, ‘You are the medical school. You are the recipients but you are also the teachers.’ We tried to inculcate in them a sense of responsibility for themselves, a social sense of attachment to the Rhode Island community. And they absorbed that; they took initiative, taking life drawing classes to understand the body not just as a medical problem but as a living entity; requesting courses in medical Portuguese and Spanish so they could speak to their patients directly; insisting that they, and we, meet our obligations to the community.

“Their uncompromising standards and questioning led to some important developments,” Aronson added, “their study of how the body is viewed in different cultural and religious traditions opened the way for development of a department of community medicine; their insistence that we examine how we treat the dying led to a course co-taught by [RIH orthopedic surgeon] Mike Scala and Brown Chaplain Charlie Baldwin in compassionate end-of-life care, which in turn planted the seeds for the first hospice program in Rhode Island. Their program of study included a more rigorous set of requirements in basic sciences than that at any other school in the country, but they were being trained in a humanistic environment in which ethical, moral, and social issues had real importance.”

1975 The Liaison Committee on Medical Education visits the Brown medical program and awards it full accreditation, contingent upon the graduation of its first medical class.

On June 2, a sunny Sunday, Brown University awards Doctor of Medicine degrees to 58 students, 45 men and 13 women—including the Charter Twelve—the first medical class since the 1820s to pursue and complete academic medical studies and clinical training within Rhode Island’s borders. The oath they take is a contemporary revision of the Hippocratic Oath, drafted by a committee of the class.

Aronson said of the inaugural class: “Their academic performance was very good; all 58 scored in the upper 25 percent on their national boards, and all got good internships. They were very bright, very dedicated to patient needs, very dedicated to Brown, and very supportive of each other. They were not competitive with one another; we didn’t encourage them to be. We had no interest in training disciples; we wanted to train equals. Neither we nor our students recognized hard borders between disciplines, and we brought in lots of social scientists—anthropologists, demographers, sociologists—and members of the spiritual, arts, and business communities, to elucidate the context in which medicine is practiced, and the ethical issues it raises. We wanted to demonstrate that medicine is more than sophisticated technologies. We encouraged our students to be open, to be skeptical, to challenge us, and they did.”

Mark Blumenkranz ’72 MD’75 MMSc’76, P’05, P’08

As best as I can tell, through the alphabetical advantage of my last name, I am the third person in the world, at least after the middle of the 19th century, to have been granted a Brown medical degree, right after Aram Arabian and Charles Bareham. As an old timer of sorts, and more recently as a member of the Corporation and chair of the Medical School Committee, I have had the opportunity to witness firsthand the beginnings of things, which were occasionally chaotic and uncertain, but always exciting.

When I arrived in 1968 I entered the Med Sci program with approximately 45 other freshmen. At that time it was a research-intensive program designed to prepare but not complete medical training. So we all entered the Brown program on a wing and a prayer, hoping and trusting, but not entirely sure that Brown would prepare us, in part, for a career in medicine. During the tumultuous late ’60s and early ’70s, we were all glad to have the extra two-year deferment from the draft and Vietnam to stay at Brown and study science, but we still worried a great deal about our future and where we would end up as doctors, if at all. There was considerable debate both within the University and at the Corporation level about whether Brown ought to be in the professional education business of having a full-fledged medical school, including what effect that would have on the quality of the undergraduate education and experience.

And in that cauldron of debate and concern, along came Stan Aronson … one of the foremost neuropathologists of his generation. While it all seems inevitable now with the bias of retrospect, it was no certainty that Brown would progress from a master degree-granting program to a medical school. And I think it would be fair to say that it may not have happened without Stan Aronson being there. His thoughtful and reassuring leadership, his patient advocacy, and ultimately his moral authority carried the day. I think if I had to try to distill the way Stan both changed and then ultimately defined medicine at Brown into a single bullet point, it would be that he put a distinctly human face on medicine.

Jonathan Gell ’72 MMSc’75 MD’75, PPhD’12

Many of us started in the Med Sci program in 1968. The clinical years started about 50 years ago. What possible remembrance of use could remain after 50 years of technological advances?

Magnetic resonance was a few maybe interpretable spikes in organic chemistry. In our rotations we treated atrial fibrillation with oubain. An MI was kept for three weeks rest as an inpatient. Beta blockers were contraindicated in heart failure. For rheumatoid arthritis the best drug was injectable gold. Trilafon was widely used at Butler for thought disorder.

What forlorn hope did our faculty cling to as they sent us on our career voyages? What heuristic value endures from those years?

Marty Felder, Milton Hamolsky, Stan Aronson, Phyllis Brown, Sungman Cha, Leallyn Clapp … those who were there can compete my ellipsis; I need to refresh my memories when I see my classmates again. What endures is they cared. Both about their work and about us. They cared about us as a class and more importantly as individuals.

What endures from Brown? Ruth Sauber was the focal point of our faculties’ hope for Menschlichkiet/Caritas. She cared for us, we were worthy.

Not immune from burnout, discouragement, or despair, but we had blessings that perhaps other institutions did not bestow. Boats in motion leave a wake. So looking back at the wake of my career voyage, I see two wings reaching to the mist or horizon. One wing out is my remembrance. The other wing is their blessing back to me.

Glenn Mitchell ’67 ScM’69 MD’75 RES’77, MPH

How do I feel about the way the Medical School has evolved over the past nearly 50 years? It would be difficult to maintain the sense of adventure that we had as the first class: the basement rooms of the then-new BioMed Center; the endless lectures and reading; and the early exposure to real patients that was a new approach back then. The hospitals and adjunct staffs were associated with the school mostly by the talents and skills of giants such as Stan Aronson, Pierre Galletti, and Levi Adams. And Stan became a second father to most of us during those heady times.

Today, we return to see a beautiful renovation of a building in what we knew as the Jewelry District across the river. It looks like a real medical school! When we talk with current students, they sound like medical students everywhere, except they seem so much smarter and even more dedicated than we were. The classes are more than twice the size of our original group, but they appear to be at least as cohesive as we were. It is a great personal joy to experience the continuity that being at the school these days demonstrates and validates. The “new” White Coat Ceremony seems like we should have thought of it. And the dean brings tears to my eyes when I see today’s students love him like we did Stan.

As we in the first graduating class come to the close of our professional practices, our original oath remains meaningful and relevant. Each year’s graduates continue to hold themselves to the highest standards of our profession. As I look back at the 45 years since my graduation, I am happy to have had a place in the long line from Hippocrates to the current First Years. The living entity of the Medical School makes me feel incredibly proud, and I want to see it thrive forever. My spouse and I decided that the best way to do that was to endow a medical student scholarship in our estate plan so the best and brightest students can continue to come to Brown and benefit from its uniqueness and its culture. It is not nearly enough to fully pay back the debt owed to the many dedicated people who educated me, but it is important to me to tangibly express my deep gratitude.

Ever True.

Christopher J. Morin MD’75, MBA

Where has the time gone? We have gained the age of wisdom and the ability to reflect on the passage of time and events. Brown and the Program in Medical Education in the early 1970s was committed to the education of the complete physician. A physician with a strong basic science foundation. An introspective and compassionate physician. A humanist and a scientist. How to achieve this goal? The journey was a mutual journey of the dean, the faculty, and the students. Who were the students of the graduating Class of 1975? We came from two MMSc classes, students who had graduated from other undergraduate colleges, and transfer students who had completed the first two years of medical school elsewhere. We were one in who we became. We were Medicine at Brown.

The faculty strove with great dedication and often with no reimbursement to provide as comprehensive an education as possible. Dr. Fred Barnes was an inspiration to me as much as Dr. Tom Randall, chief of surgery, or Milt Hamolsky, chief of medicine at Rhode Island Hospital. Dr. Martin Felder at The Miriam Hospital with Dr. Bob Hopkins. George Vaillant came down from Harvard and provided a series of medical encounters with actors to help us learn how to interact with patients, from the patient’s perspective. Whether the professor was a full-time faculty member, chief of service, or a voluntary clinical faculty, the commitment to us was exceptional. The faculty took great pride in the maturation of their students as we became physicians.

What does it mean to be a Brown-educated physician? What would it mean 50 years from now? Those were questions that we asked ourselves. How did we answer them? By becoming highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and researchers. Did Brown succeed? Did we succeed? Yes, we did!

Graduating from Brown with the MD Class of 1975, I journeyed to Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School for my surgical training. How did I get there? By not only the education I had received but by the support of the faculty at all levels. By alumni who looked to foster Brown’s development. How did my education at Brown compare to the preparation of the graduates of Harvard Medical School? We were at least as well prepared if not better.

During the 1980s and ’90s I had the honor of being on the clinical faculty of Brown, and serving in the leadership of the Brown Medical Alumni Association as its first president who had graduated from the Medical School. The commitments of the students and faculty remained the same to educate humanistic scientists who put service to humanity first. Brown succeeded and continues to succeed in this goal.

Patricia L. Myskowski ’72 ScM’74 MD’75 (with Alexander J. Swistel MD’75)

My memories of Brown—and in particular being a “Med Sci”—begin in the spring of 1968, when a gaggle of awkward yet oddly confident teenagers gathered on the Green for a campus tour. My prospective classmates and I were invited up to campus for a pre-admission weekend, and it was supposed to be a recruitment weekend of sorts. My interview with a gastroenterology professor was interesting—from “Do you have a boyfriend?” (“Yes”) and “What about your children?” (“Sir, I am 17 years old and I don’t have any children”) to his conclusion that I was committed enough and that he would see me again in his course in five years (which he did). My fondest memory of the weekend was meeting Valerie Parisi ’72 MD’75, in a bright yellow dress, whom I recognized as a force of nature and faithful friend from the moment we met.

Our time as undergraduates in the Med Sci program cannot be separated from the turbulent times at Brown: Pembroke’s merger, Ira Magaziner’s New Curriculum, the campus strike. Still, we remained a somewhat cohesive group-within-a-group, us Med Sci’s. Then came the preclinical years: tough (Dr. Erickson’s anatomy course), but with a growing sense that our class was special. Our faculty was supportive in a way not known to most medical students. Our class was never told that there was anything we couldn’t do—and so, in our professional lives, many of us have achieved far more than we would have ever predicted (e.g., medical school deanships, a Lasker award).

My personal life took its most important turn when I signed up to give a tour to the incoming third-year medical transfer students and met Alex Swistel. We married after internship and have spent nearly 44 years in New York City with children and now grandchildren. We are still working: me with almost 40 years at Memorial Sloan-Kettering, and Alex at NewYork-Presbyterian. Weill Cornell Medicine has become our academic home: professor of dermatology for me, and endowed professorship in breast cancer surgery for Alex. Neither one of us was a “star” in the class and we could never have predicted where we would be today. But our Brown Medical School experience, as the first class, was unique and empowering in a way we could only later appreciate. My hope for future classes is the same legacy.

Daniel Small ’71 MMSc’73 MD’75

I was a member of the “Charter 12.” Originally our program was to culminate in a MMSc degree and we would transfer to another medical school for our clinical work and our MD degree. (Most people finished at Harvard.) We were introduced to our first patients in our freshman year in college and we had a seminar program through our six years led by Fred Barnes, MD, where we had monthly evening lectures from professors at Brown who told us about their interests in life. Our psychiatry training was enhanced by Dr. George Vaillant from Harvard coming down and viewing with us plays performed by the Trinity Repertory Company in a dorm lounge. Dr. Valliant, the actors, and our class discussed the psychological mechanisms in the play. We were so impressed with the interest in us that was shown by the medical school faculty that we asked to stay on at Brown and be the guinea pigs for the clerkship programs.

The administration embraced our request and asked many of us to serve on committees for the new MD program. I served on the admissions committee and I found that my recommendations on prospective candidates were given strong consideration.

I completed my coursework in 1974 and found a little-known law in Rhode Island that you could practice medicine if you were affiliated with a hospital and had three and a half years of medical school training but did not have an MD degree. This law allowed Italian physicians fleeing fascism in the 1930s to come to Rhode Island and practice medicine for the Italian community. I approached Paul Calabresi, MD, about doing my internship at Roger Williams General Hospital before my MD and he approved. John Horneff ’71 MD’75, Brent Davis ’71 MD’75, and I were the first Brown University-trained house staff in the Brown system.

As part of our internship we rotated through the Providence VA Hospital. It had been set up as a clinic with an overnight hotel. Within one week of being there we transformed it into an actual hospital with lab and X-ray services available 24 hours and we were able to wrestle the beepers away from the housekeeping staff and distributed them to the house staff.

After my internship and residency year in medicine I did my rheumatology fellowship in a combined program at Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation and University of California San Diego (never had to go through the Match). I entered practice in 1978. I have been in a number of practice settings and have had a career-long interest in Sjogren’s syndrome. In 2015 the Sjogren’s Syndrome Foundation awarded me their national Healthcare Leadership Award. I am currently working in the Mayo Clinic Healthcare System, where I am chair of the Department of Rheumatology at Franciscan Mayo.