A new test could detect early signs of Alzheimer’s in saliva.

Saliva may carry indicators of Alzheimer’s disease and offer a new method of early diagnosis, scientists say.

A team of researchers at Brown is analyzing patients’ gene expression through saliva samples in hopes of finding differences unique to preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, which could then be used for early diagnosis, explains a principal investigator of the study, Jill Kreiling, PhD.

“By the time people come into our clinic, the patients themselves have experienced life-altering changes in their functionality,” adds study investigator Jonathan Drake, MD, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders Center (ADMDC) at Rhode Island Hospital and an assistant professor of neurology.

The center is trying to raise awareness that “there’s a way to try to get [an]early diagnosis so we can offer early treatment and prevent it from getting worse,” adds Chuang-Kuo Wu, MD, PhD, the director of the ADMDC and a professor of neurology.

Amyloids and other proteins responsible for Alzheimer’s are deposited in the brain decades before symptoms manifest and a diagnosis can be made. Drake and Wu say that a biomarker, or indicator, for the disease could help with its management and, as treatments become available in the future, improve therapy and outcomes.

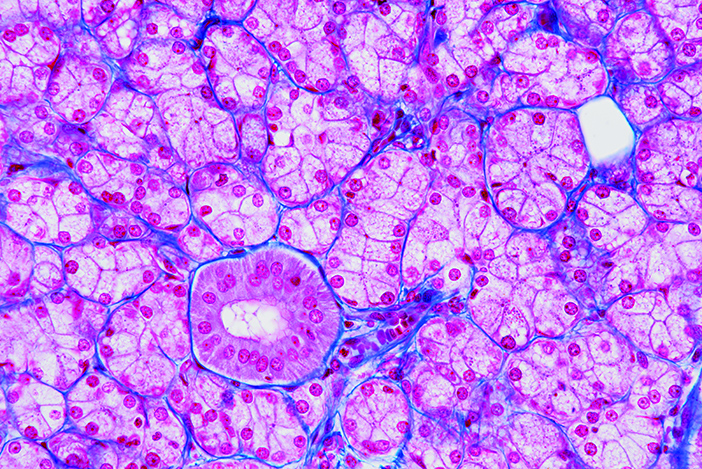

Saliva contains exosomes, or extracellular vesicles, which carry RNAs and proteins from cells. Certain nerves travel from the brain to glands in the face that make saliva, says Kreiling, an associate research professor of molecular biology, cell biology, and biochemistry. Using these nerves as tracks, vesicles in the brain may slide down until they end up floating in the saliva.

Peter Quesenberry, MD, the Paul Calabresi, M.D., Professor of Oncology and a professor of medicine, has studied this mechanism in people with head injuries. He proposed investigating it in AD patients and is another PI of the study.

Saliva is easily retrievable and does not involve the skills, financial costs, and patient discomfort associated with other tests for Alzheimer’s, like brain imaging, blood tests, or spinal fluid analysis. This makes the method accessible in low-resource settings. Collected saliva is screened for expression of genes in the brain by examining exosomal RNAs. Genes with significantly different levels of expression in patients with Alzheimer’s compared to healthy patients could become diagnostic markers, Kreiling explains.

To determine whether a correlation between vesicle RNA content and Alzheimer’s exists, researchers are matching data from study participants’ saliva samples with results from blood sample analyses currently used for diagnosis, Kreiling says. The findings from research participants who already have an Alzheimer’s diagnosis will be compared to those from participants with normal cognitive function and no AD diagnosis to pinpoint differences.

The researchers aim to use the exosome data to determine risk of Alzheimer’s in study participants who do not yet have cognitive symptoms of the disease, and then observe their health for five years to see whether the disease manifests as predicted, Kreiling says. In practice, such early diagnosis could inform care for Alzheimer’s.

The team hopes to eventually study this method of exosome analysis in the context of other conditions and neurodegenerative disorders, like other dementias, Parkinson’s disease, and ALS.

Beyond diagnosis, the findings from this research may pave the way for new treatments. “When we look at vesicles and see what transcripts are changing, this may give us some insight into the pathology that may perhaps then allow us to identify different therapeutic targets,” Kreiling says.