New research into how Candida albicans colonizes the human GI tract suggests ways to treat difficult infections.

New research sheds light on how a fungal pathogen colonizes the human gastrointestinal tract—and offers clues on how to potentially treat certain fungal infections.

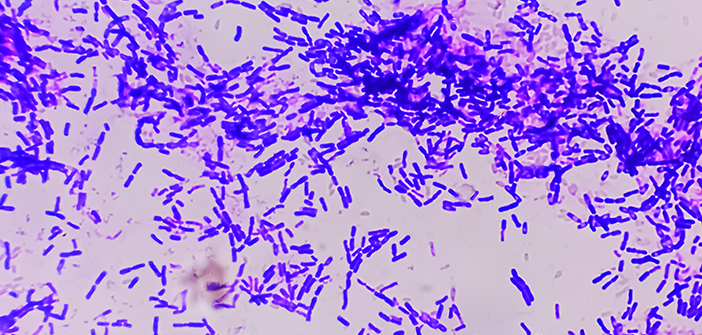

The study, published in Nature, explores Candida albicans, a naturally occurring fungus in the human gastrointestinal tract, and the role of its secreted toxin, candidalysin, in promoting the fungus’ colonization of the gut. C. albicans is linked to bloodstream infections that have high mortality rates and can be challenging to treat, says senior author Richard Bennett, PhD, chair of molecular microbiology and immunology.

“C. albicans can escape the gut and then disseminate throughout the body, infecting many different human organs—even the brain,” he says.

Coauthor Shipra Vaishnava, PhD, associate professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, adds that while fungi usually help our immune system, this isn’t true for all species. “Some Candida species, including C. albicans, can cause serious infections in people with weakened immune systems,” she says. “Understanding how C. albicans thrives in the gut is crucial, especially when fungi coexist with many bacteria.”

Bennett says scientists have long known that C. albicans can grow both as single-celled yeast and as multicellular hyphae. Previous research had shown that the yeast forms were better at colonization, and hyphal forms less so, but most of those studies used mice given antibiotics to clear out competing bacteria and help the fungi to colonize the gut.

For the new study, Bennett’s lab evaluated fungal colonization in the presence of bacteria in mouse models, either by not using antibiotics in mice naturally colonized with bacteria; using germ-free mice that were subsequently colonized with bacteria; or using antibiotic-resistant bacteria to colonize mice given antibiotics.

Previous studies established that the yeast-to-hyphal transition is critical for Candida to cause disease, and that the hyphal form secretes candidalysin, which enables it to damage and invade host cells, says Bennett, who is also the Charles A. and Helen B. Stuart Professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology. The new findings show that both yeast and hyphal forms are critical for Candida colonization, he says.

“Every time bacteria were present in the gastrointestinal tract, and if the Candida cells were locked into the yeast state, they would be outcompeted by wild-type Candida cells that could filament,” Bennett says. “Our results highlight that Candida needs the ability to switch back and forth between yeast and filamentous states to colonize a mouse gut when normal levels of bacteria are present.” He adds, “As soon as you have high levels of bacteria present, Candida will utilize both yeast and hyphae forms to be able to efficiently colonize the gut.”

Additional experiments revealed that candidalysin exhibited anti-bacterial properties, which enables the hyphal form to compete with other bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, Bennett says.

The data suggest that blocking the ability The data suggest that blocking the ability of to form hyphae could also reduce its colonization. Colonization is linked to gut inflammation and disease, as systemic infections can arise when fungal cells escape the gut; reducing or eliminating C. albicans could block that cycle of infection.