A new study explains why it’s difficult to predict the evolutionary fate of a new genetic trait.

The phrase “survival of the fittest” makes the principle of evolution by natural selection easy to understand: individuals with a trait that adapts them well to their circumstances are more likely to pass that trait along. But as a new study explains, multiple factors make predicting the fate of a trait fiendishly difficult.

Not only would improved predictive models help scientists better model how evolution works, but also they could aid in efforts to prevent infectious diseases. Every year, for example, vaccine makers, epidemiologists, and physicians strive to predict where diseases such as influenza, Zika, HIV, and Ebola may be headed next.

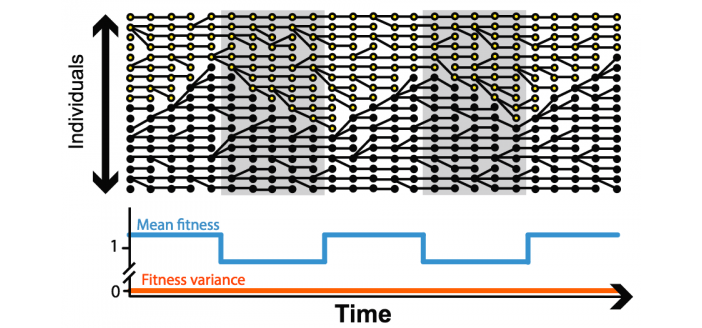

Fundamentally, the problem is that a trait conveyed by a gene variant, or allele, may be advantageous for one or a few generations, but provide no advantage or become a liability when circumstances change, says senior author Daniel Weinreich, PhD, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and co-director of the EEB graduate program.

But most theoretical models of population genetics assume that fitness remains constant. “We are articulating a number of different biological contexts in which the fitness of an allele might change over its ‘lifetime’ or lineage in a population,” Weinreich says. “We are convinced that the other contexts, where it is constant, are the exceptions, not the rule.”

The new study in the Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics provides an overview of what complicates predictive models and how scientists are trying to make progress, for the benefit of public health, among other areas.

“Infectious diseases experience constantly varying selective pressures as they spread within and between hosts and encounter drugs and host immune responses,” lead author Christopher Graves PhD’17 says. “Understanding how evolution proceeds in scenarios of highly variable selective pressures will increase our ability to predict drug resistance and disease outbreaks and ultimately lead to the creation and deployment of more clever drug and vaccine strategies.”

Continue reading here.