Canine ancestors evolved with climate change.

Old dogs can teach humans new things about evolution. Fossil evidence suggests that, as North America’s forests gave way to grasslands over millions of years, dogs adapted their hunting style to suit their changing habitat.

“It’s reinforcing the idea that predators may be as directly sensitive to climate and habitat as herbivores,” Christine Janis, PhD, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, says. “Although this seems logical, it hadn’t been demonstrated before.”

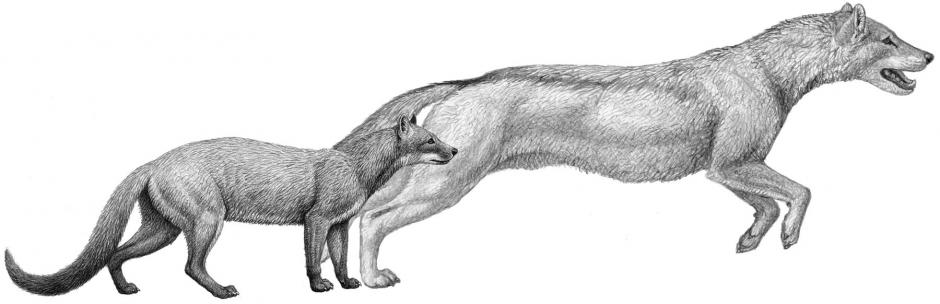

Dogs are native to North America. Their ancestors 40 million years ago looked like mongooses and were well adapted to the warm, wooded environment of that time. Their forelimbs were not specialized for running, and had the flexibility to grapple with whatever meal unwittingly walked by.

But a few million years later, as the global climate began to cool and the continental interior dried, forests slowly gave way to open grasslands. By examining the elbows and teeth of 32 fossil canids, Janis and other researchers found clear patterns: as climate change opened up the vegetation, dogs evolved from ambushers to pursuit-pounce predators like modern coyotes or wolves.

“The elbow is a really good proxy for what carnivores are doing with their forelimbs, which tells their entire locomotion repertoire,” Janis says. Dogs’ front paws, which once could swivel to grab and wrestle prey, evolved to always face down, specialized for endurance running. In addition, the dogs’ teeth trended toward greater durability, all the better to eat prey that had been rolled around in the grit of the savannah, rather than on a damp, leafy forest floor.

The study, published in Nature Communications in August, suggests that predators don’t develop forelimbs for speedy running simply because their prey run faster. Though herbivores were evolving longer legs, the canine evolution evident in the fossils tracked in time directly with the climate-related habitat changes. After all, Janis says, it wasn’t advantageous to chase and tackle prey until there was room to run.

“There’s no point in doing a dash and a pounce in a forest,” she says. “They’ll smack into a tree.”