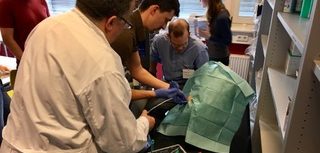

Medical students get critical care training in Tübingen, Germany.

What do Goethe, Hegel, Kepler, Alois Alzheimer, and Pope Benedict XVI have in common? At some point in their careers, they either studied or worked at the University of Tübingen. Founded in 1477, nearly 290 years before Brown, the university is one of the oldest in Europe and is one of the most enchanting. Situated in the beautifully preserved medieval town for which it is named, near the fabled Black Forest and some 20 miles south of Stuttgart, the university has long been known for its theologians and scientists. For instance, the Stiftskirche, the oldest and largest church in Tübingen, was one of the first to convert to Lutheran Protestantism, shortly after its completion in 1470. And it was in the kitchen of the Schloss Hohentübingen (Tübingen Castle) where nucleic acids were first isolated, by Friedrich Miescher, who in 1869 used an innovative technique to extract and purify DNA from white blood cells.

It was in this storied setting that five members of the MD Class of 2017—three fresh off the residency interview trail (including me) and two directly from their honeymoon in Mexico—gathered for two chilly weeks in February, to attend Winter School. This annual international exchange course on critical care medicine is hosted by Reimer Riessen, a professor of critical care at Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, or the Tübingen Faculty of Medicine, one of the leading medical centers in Europe. We were joined by three medical students from the University of Kyoto and eight from the University of Tübingen for didactics, clinical skills workshops, simulations, and discussions on the practice of medicine in our respective countries. Conducted in English, the centerpiece of the course was the Fundamental Critical Care Support Program, a curriculum established by the Society for Critical Care Medicine and for which my fellow students and I received a certificate after passing a comprehensive written exam on our final day.

Morning didactics were led by Dr. Riessen and other Tübingen faculty members, as well as Brown’s own Assistant Professor of Medicine Matthew Jankowich, MD, and Pulmonology and Critical Care fellow Amanpreet Kaur, MD F’17, both excellent and enthusiastic teachers who joined us for the whole course. These interactive lectures focused mostly on evidence and theory pertinent to critical care, including acid-base analysis, neurologic support, life-threatening infections, acute coronary syndromes, and numerous other high-yield topics. Afternoons involved more practical, hands-on experiences. These included rounding in two large, high-acuity medical and surgical intensive care units, where students broke into small groups to see patients and learn about invasive monitoring, mechanical ventilation, and the management of shock. Students also received detailed instruction in conducting bedside ultrasound assessments and gained valuable practice using several state-of-the-art sonography machines, which the university had purchased exclusively for teaching purposes. Participants also were guided through chest tube placement, establishing central venous access, and obtaining arterial blood gases, first using dummies, and later during a cadaver workshop in the university’s impressive, technologically advanced anatomy lab.

SANGFROID

When not learning how to stabilize acutely ill patients, we had ample time to get to know our international colleagues. As is common throughout Germany, most medical students and faculty take a proper, sit-down lunch in the hospital cafeteria, which provided a daily opportunity to share our stories and perspectives with one another. Over traditional Swabian cuisine, including staples like Käsespätzle (a cheesy noodle dish), Maultaschen (a kind of mincedmeat-filled dumpling), lentils, and sausage, we compared the different approaches to medical education in our countries. Both Germans and Japanese begin medical school after high school and spend six years before moving on to pursue general training in medicine or surgery. Many in Germany take on part-time jobs in research labs or skilled nursing facilities to help pay for living expenses, though their medical education is entirely free. In Japan, fewer take jobs, and tuition is typically only a few thousand dollars per year. Both Japanese and German medical students commented how American medical students seem to be given more responsibility and to have more direct interaction with patients during their clinical rotations, perhaps in lieu of some additional didactic instruction.

We also made several outings as a group, including a visit to the massive, Guggenheim-like Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart and a tour of Hohenzollern Castle, a popular tourist destination in a nearby town. Probably the most memorable event involved learning to bake traditional Swabian pretzels at a local bakery in Tübingen from a man who’d been baking for more than 30 years, and then getting to take the tasty, aesthetically pleasing results back to our guesthouse by the bag full.

During the last two days of Winter School, we worked together and put our skills to the test during a series of simulations at TüPASS (Tübingen Patientensicherheit und Simulation), the university’s anesthesia-run center for patient safety and simulation. After lectures on airway management and advanced cardiac life support and some practice with intubation skills, we were oriented to a room fully equipped with everything you would find in a modern ICU, plus a dummy capable of producing its own heart and lung sounds, mimicking a difficult airway, and expressing neurological symptoms such as mydriasis. We split into teams, each with at least one American, German, and Japanese student, and took on assigned roles: lead doctor, two nurses, a respiratory therapist, and a consulting physician. Meanwhile, the rest of the class watched and listened from the lecture hall via remote video feed. Teams encountered a range of simulated clinical scenarios, from post-operative pulmonary embolism to septic shock to even a team member syncopizing during a code.

After each simulation, we had the opportunity to review highlights of our performance on a video recording and discuss what did and didn’t go well. We learned several things from this experience: the importance of teamwork and of having designated roles and sticking to them; closed-loop communication; and techniques to keep patients safe and error to a minimum. We also developed trust in each other and a great deal of respect for our international colleagues.

I am looking forward to bringing these lessons to bear in my career. As someone interested in an academic career in anesthesiology and critical care, my two weeks in Germany working with Brown, Kyoto, and Tübingen colleagues were some of my most formative.