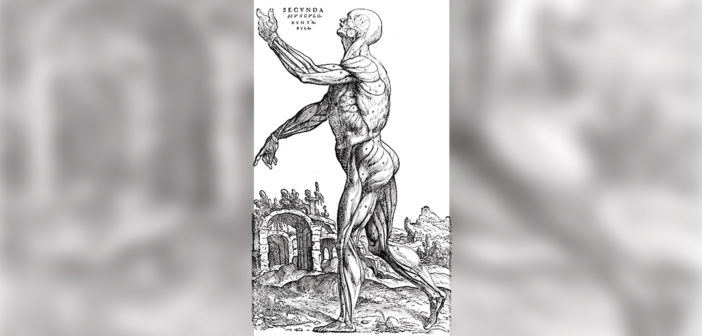

Exploring the legacy of Vesalius, the ‘physician-artist.’In college, I took a course titled Bodies of Knowledge: Renaissance Art and Anatomy, which might easily have been called The Art of Medicine. Among others, we studied the works of Michelangelo, Da Vinci, and Vesalius, the 16th-century Flemish physician who created the definitive anatomy textbook of its time, De humani corporis fabrica (“On the fabric of the human body”). Vesalius was the quintessential “physician-artist”—an individual whose work as an artist and a physician was completely intertwined.

The “art of medicine” was also a theme in an afternoon class I took as a first-year med student during which François Luks—a medical illustrator and pediatric surgeon—showed us how he creates the images that accompany his publications. I’ve seen the phrase employed as the title for exhibitions of either art produced by doctors or photography involving medical subject matter, like microscopic images of neuronal connections, or an exhibit about the development of stains used by pathologists.

Most of these examples are literal in their perspective. With the exception of Vesalius, many of them portray art as part of a left-brain, right-brain dichotomy between physicians’ creative sides and their scientific sides, a yin and yang relationship, with the omnipresent idea that doctors must—perhaps for their own sanity—preserve creative outlets.

More and more, these two inner lives are depicted as being in conflict. This conflict may come from the concept—in medicine and outside of it—that being a physician is not simply a vocation, but rather a calling. This view, while ennobled, has been restrictive, leading doctors to feel they have to fight to experience the more creative aspects of their selves: their identities as poets, writers, actors, painters, or craftsmen. And this is increasingly so in a time when algorithms are dominating decisions, and work and lives are edging from the qualitative to the quantitative.

The origin of the phrase can likely be traced back to one of the most famous ancient physicians, Galen, who wrote Ars Medica (“Art of Medicine”) in 100 or 200 CE. In his treatise, Galen describes mental properties and argues his hypotheses based on animal dissections. Galen was more likely referring to the technical skills and the craft that physicians employ to make discoveries and treat patients.

In the modern lexicon, the phrase “the art of medicine” has come to define the so-called soft skills involved in treating patients—abilities that we learn in our Doctoring course at Brown. Doctoring focuses on both physical exam and interviewing skills as well as building rapport with patients. This is how I’ve often heard the phrase employed, especially while talking about the talent required to be an effective and trustworthy physician. These soft skills, such as empathy, listening, and attentiveness, foster the doctor-patient partnership, an alliance highly touted by medical schools, and especially at Brown.

The phrase “soft skills” itself connotes a dichotomy, between the soft and less quantifiable skills of communication, empathy, and compassion, versus the hard and more quantifiable skills of lab interpretation and analysis of CT scans or X-rays. The term “soft” can also evoke either a sense of comfort and familiarity, or an idea that these skills are less important or less difficult.

I don’t feel the polarity between hard skills and soft skills or the humanism of doctoring conflicting with the science of medicine. I fervently believe that there is an art to medicine, in the sense that being a great physician involves a critical combination of book learning and hands-on experience, skills that are learned inside the classroom and outside, and a combination of instinct and intuition, backed by evidence-based medicine.

There are many parallels between my training as a doctor and my education as a writer. Both require skills that I find come naturally to me, as well as ones that are more challenging. For me, both involve forging connections and telling stories, both require repetition and practice. As a student-doctor, I rely on the perspective of more experienced physicians to help determine next steps, organization, and understand key themes, while as a writer I rely on my editors and readers for those same three things.

While my career will focus on clinical practice, I am also passionate about health communication, health literacy, and science journalism. For me, there is no dichotomy or contradiction to wrestle with: science journalism is not separate from my passion

for primary care, but rather an extension, a means of expressing my advocacy for patient empowerment and engaging the broader community in discussions about health care and the integration of science and other medical disciplines into everyday life.

That’s why I came to Brown for my medical training, because it is a place where I could learn and practice Ars Medica, where I could embrace both the ancient and the modern definitions of the art of medicine, and combine creativity with science. It is a place that embraces both denotations of the art of medicine.